Empire Corridor History

Empire Corridor History

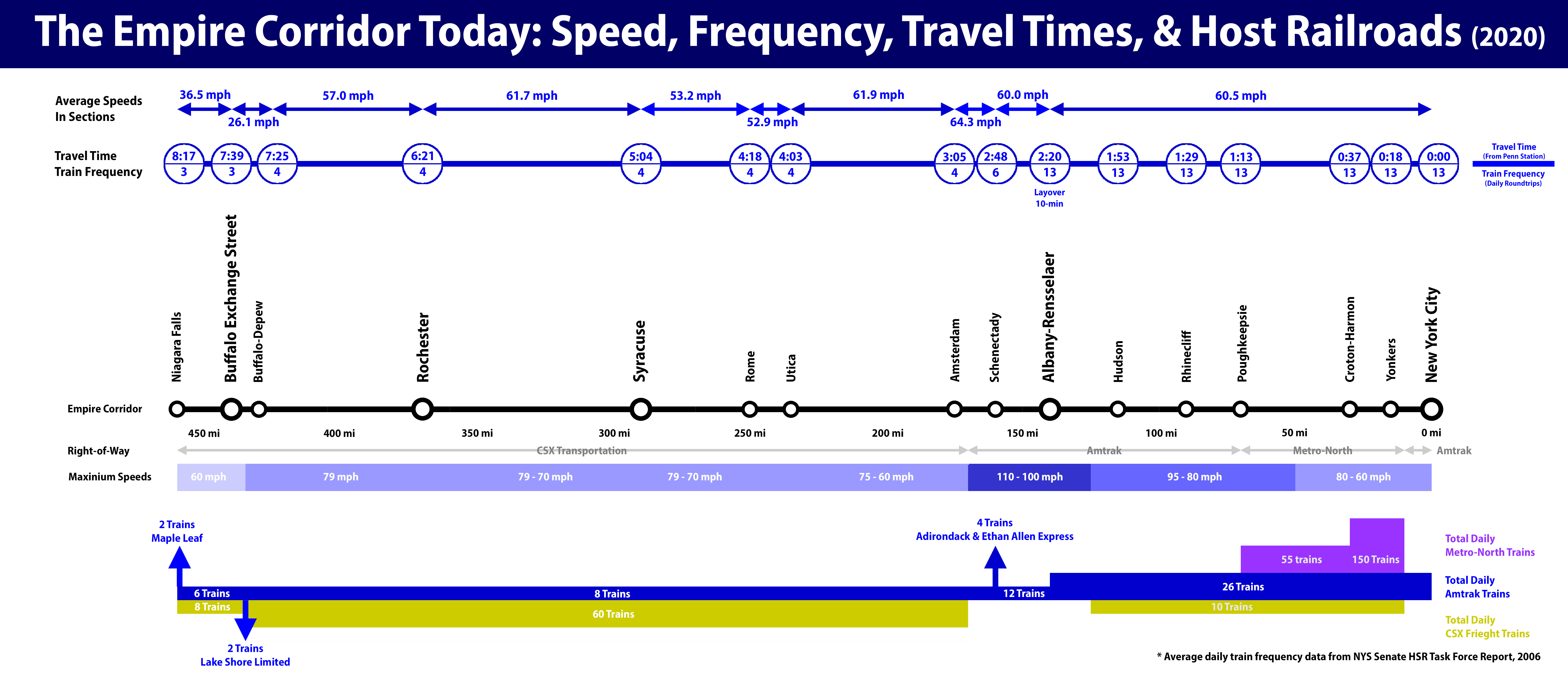

The Empire Service is the primary service component of the Empire Corridor, a “higher speed” intercity passenger rail corridor stretching from New York City north along the east bank of the Hudson River to Albany, then west across Upstate New York to Buffalo and Niagara Falls

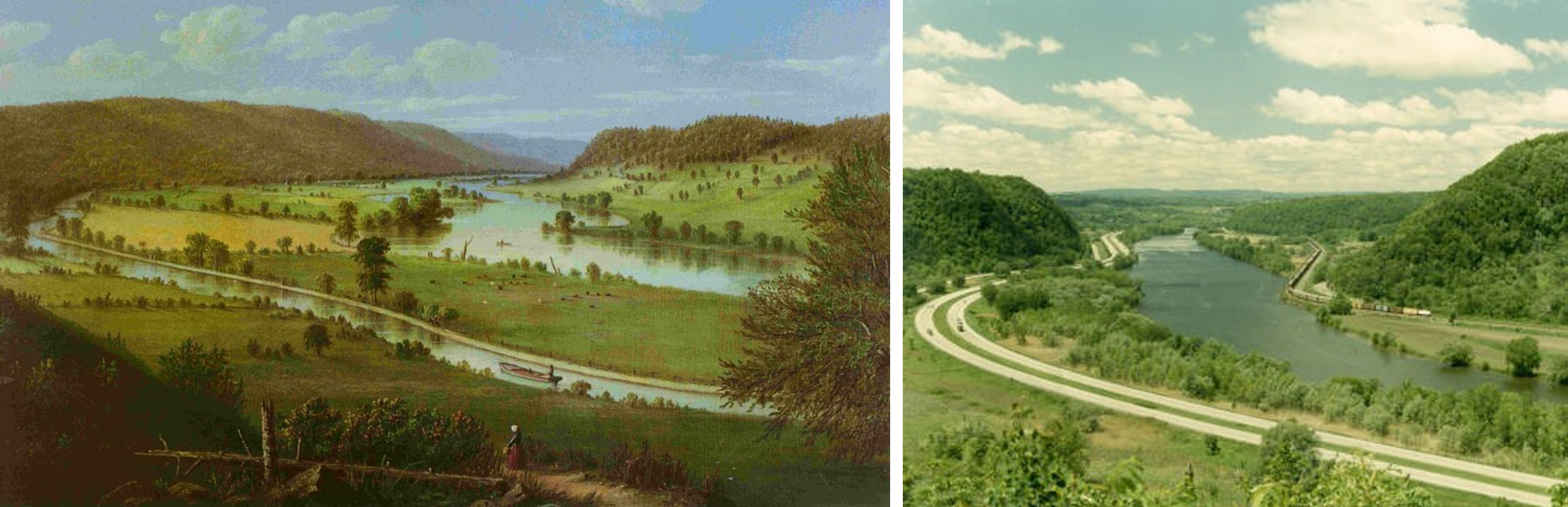

LEFT: Early View of the Erie Canal and the Mohawk River looking west up the Valley. RIGHT: A mid-20th century view of the Mohawk Valley view with (L to R) the NYS Thruway, Mohawk River/NYS Barge Canal, and former New York Central mainline.

The Story of an Pioneering Intercity Passenger Rail Corridor

TODAY'S Amtrak trains follow the natural pathway of the Hudson and Mohawk valleys, a “Water Level Route” carved by glaciers during the last ice age through the formable barrier of the Appalachian chain of mountains stretching from Alabama to Maine. First utilized by the Native American tribes and then European colonists, trade on foot and in canoes moved between the eastern seaboard and the continental interior.

Following the Independence of the United States, steam navigation, canal barges, and then steam trains revolutionized trade and travel, becoming the catalyst of intensive agricultural and industrial development of Upstate New York, with great cities of commerce and education including Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo rising up from the former wilderness by the American Civil War. The 19th century story of the formation of the Hudson River Railroad and of the railroads across Upstate are covered in depth here in these PDF articles. With the progress of technology, rail travel got better and better, reaching its high-water mark of success in ridership during the end of the Second World War.

Since then, the canal and railroad have been joined by the interstate highway, while jet planes fly over the rolling countryside. New transport technology threatened to make the passenger train go the way of the steamboat and stagecoach. To avoid that passenger rail service had to be rethought with innovation in both operations and technology embraced and put in practice.

While fast and frequent corridor service was most effectively enacyed overseas — famously seen on a large scale in Japan with the Shinkansen “Bullet Train”, France with its TGV train network, and Amtrak with its Northeat Corridor services — this is the story of how on a smaller scale that was done with the Empire Service of New York State, which unlike perhaps the many high-speed rail projects undertaken overseas since the 1960s, very much remains a work in progress.

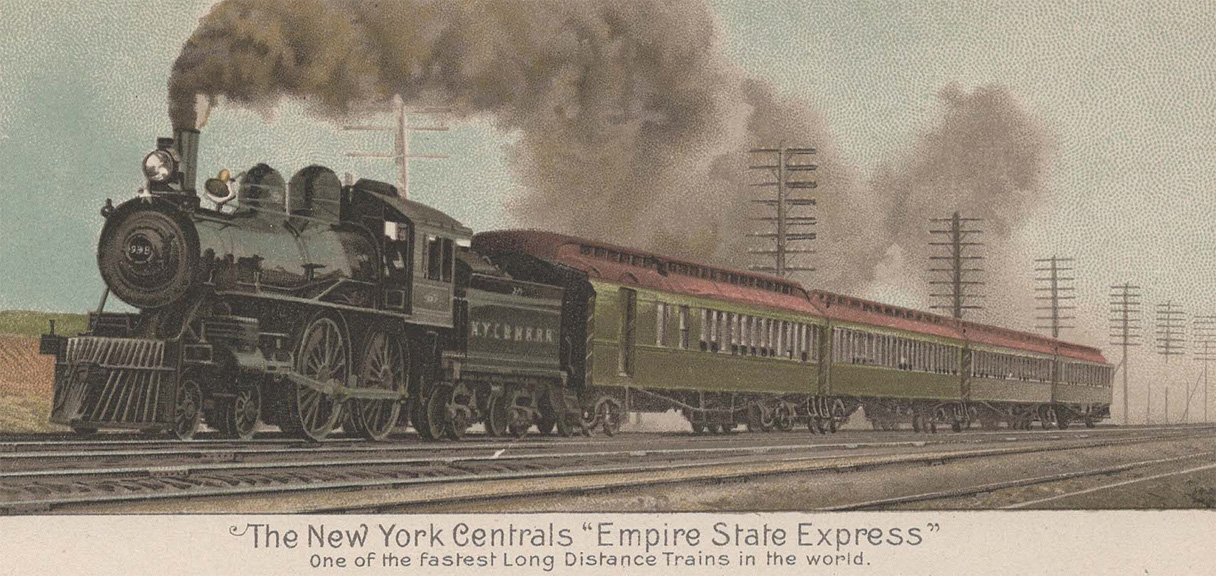

Serving many of the most populated and industrialized states in the country between New York City, Boston, Buffalo, Chicago, and St. Louis, the New York Central ran extensive passenger serives including luxury high-speed express strains like the Empire State Express and 2oth Century Limited. With famous Engine 999 at its head the Empire State Express set a speed record in 1893.

Birth of the Empire Service

THE PRINCIPAL passenger & freight rail route across New York State was that of the New York Central Railroad (System), which owned and operated the trackage which is used by Amtrak’s Empire Corridor trains today.

The heyday of the New York Central’s passenger service came during World War II and in the years immediately following the war. Multiple overnight trains (including the fabled Twentieth Century Limited) departed New York’s Grand Central Terminal each day for major cities in the west, including Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati & St. Louis. And numerous day trains served the Upstate NY cities including Poughkeepsie, Schenectady, Utica, Syracuse, and Rochester along the four-track mainline to Buffalo. During WWII the Central committed to a large investment in new passenger equipment, creating the “Great Steel Fleet” of 33 streamline trains.

But as was the case with all passenger train service across the country, the rapid growth of air travel and the construction of the Interstate Highway System in the Postwar Era decimated the railroads historic domination of the intercity passenger travel market. Ridership dramatically fell as the public flocked to highways and the airlines, both modes of transport taking advantage of the latest technological innovations while also being lavished with generous government subsidies. The New York Central, like most railroads of the time, found itself heavily supporting its unprofitable (and highly governmentally regulated) passenger trains from the revenues they made on freight.

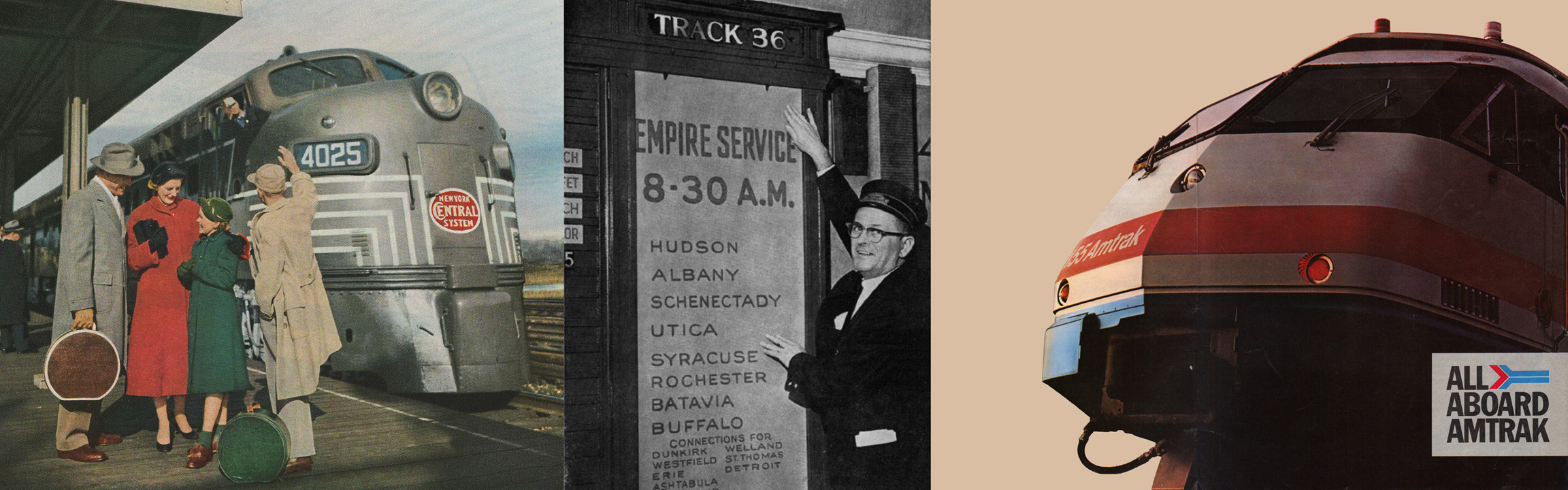

Colorful print advertising from the 1950s for the New York Central's long-distance intercity passenger service.

By the mid 1950’s, the facts were obvious to the Central’s management that their intercity passenger services would have to be radically re-organized if any passenger trains were to survive. After extensive research the New York Central’s Passenger Department’s in the mid-1950s reached conclusions and made recommendations that pioneered many of the concepts of intercity rail service that today have long been standard practice in Europe and Asia since the 1960s.

The Passenger Department proposed the creation of what we now call a “Corridor Service”. In place of a few long-haul trains made up of coaches, sleepers, dining cars, and the “head-end” traffic of baggage, mail, and express freight, a new timetable pattern of fast and frequent regional passenger trains scheduled at regularly intervals through the day would be created.

The first attempt to put this new operating theory into practice was the “Travel Tailored Schedules” of 1956, the first of a planned series of changes to transit from long-haul to short-haul trains system wide. However, this scheme was aborted due to opposition from the railroad's Freight Department which didn’t want the interference that a fleet of short but faster and more frequent passenger trains could create with slower and longer freight trains.

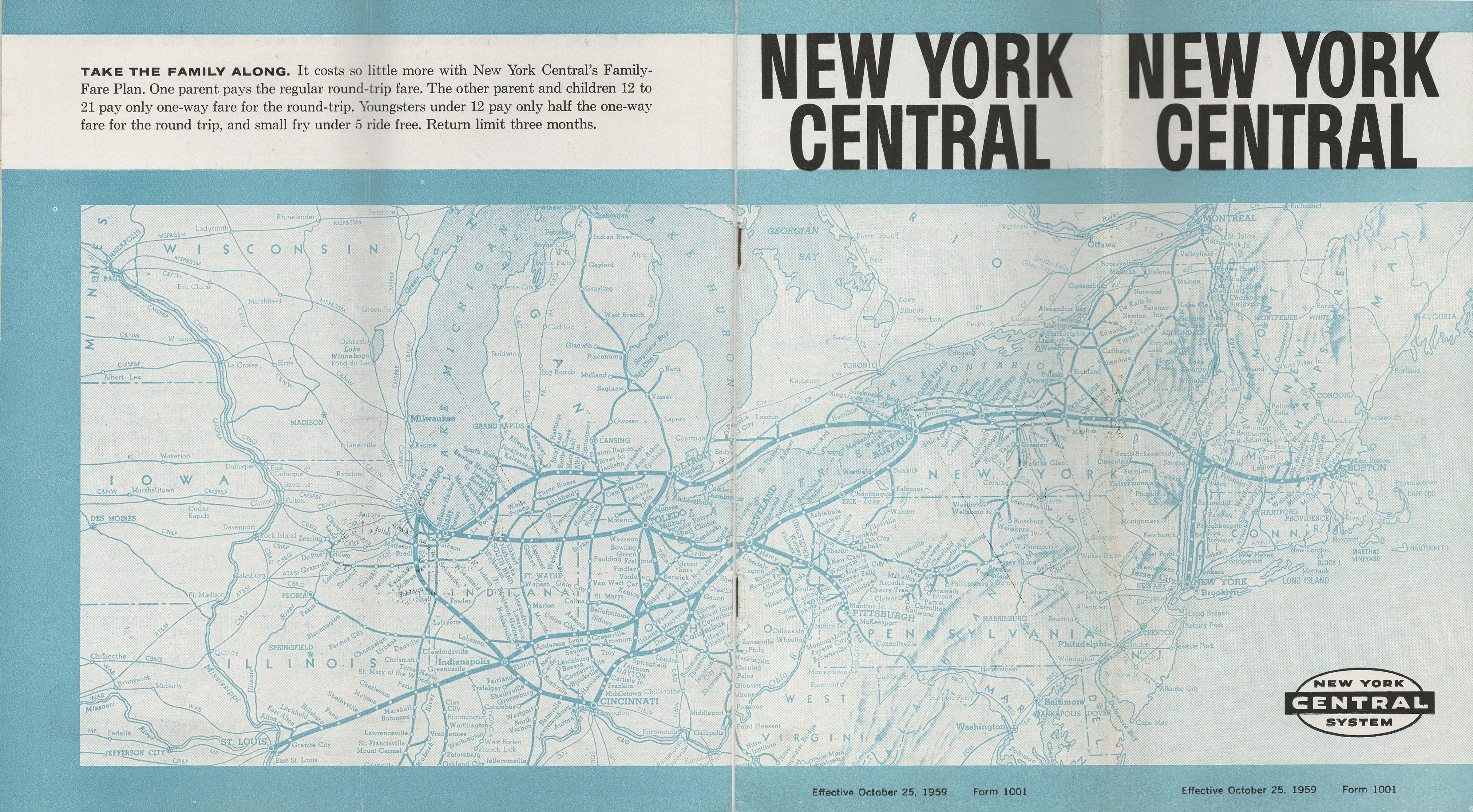

ABOVE: The New York Central System passenger timetable from October 1959. BELOW: 2oth Century Limited along the Hudson River.

In 1957 the passenger deficit for the Central reached $52 million. The railroad into the 1960s slowly consolidated its intercity passenger service, mostly of long-distance trains stretching from New York and Boston to Cleveland, Detroit, St. Louis, and Chicago. The 66 passenger and mail trains across Upstate New York in 1951 was cut to only 14 by 1965. By 1967 the passenger deficit had been cut down to $28 million, but things got worse when midyear the U.S. Postal Service ended its Railway Post Office (RPO) operations that brought in $7.8 million annually.

As railroad author Fred Frailey detailed in his authoritative book “Twilight of the Great Trains”, passenger trains that had been making an above-the-rail “operating profit” pre-1967 fell deep into the red without the “head end” traffic of mail and express parcels. The remaining mail traffic could be handled by dedicated non-passenger mail trains.

While seemingly maintaining the quality of it’s top trains like the 2oth Century Limited, the Central and other railroads systematically initiated policies to downgrade most of the others, thus leading to even lower ridership & revenues. The ploy (which largely worked) was to demonstrate to governmental regulators that the American public was truly done with passenger trains and in order to save the entire railroad industry, most trains and routes would have to be abandoned.

Following the loss of the mail contracts in mid-1967 the New York Central applied to the New York State Public Service Commission for its approval to dramaticly reduce its intercity passenger service in Upstate New York. The railroad wanted to axe many of its surviving intercity passenger trains, including 5 of the 9 remaining long-distance trains traveling between New York City and Buffalo.

ABOVE RIGHT: The inaugration of the Tokaido Shinkansen in Japan before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics with its 130-mph "Bullet Trains" breathed new life into passenger rail, encouraging a number of high-speed intercity passenger modernization projects around the world. ABOVE LEFT: In America the US Goverment and Pennsylvania Railroad partnered on the Metroliner – the predessor of today's Acela Express – which enter service on January 16, 1969.

But New York State regulators were not ready yet to give up on the idea that passenger trains could (if properly operated and marketed) serve an important transportation role for the citizens of the state. The New York Central smartly recognized that if they were to be successful in ridding themselves of most of their remaining overnight trains, they would have to at least make an attempt to provide an improved daylight service across Upstate New York.

Thus, the railroad came back to the commission with a counter-proposal to replace the existing intercity passenger service including the famous but increasingly shabby 20th Century and the Empire State Express between New York City and Buffalo with a restructured daily schedule of faster and regularly intervaled trains, the Central finally putting theory and plans first developed in the mid-1950s

The new service plan was ultimately approved by the regulators. On Saturday, December 2, 1967, the Central’s last-named trains (including the Twentieth Century Limited) made their final runs. The next day, Sunday December 3rd, 1967, saw the start of the Central’s new “Empire Service” with the 8:30am departure of train #71 from Grand Central’s Track 36. That evening, nameless train #61 departed Grand Central at 6:30pm for Chicago; the only overnight service remaining.

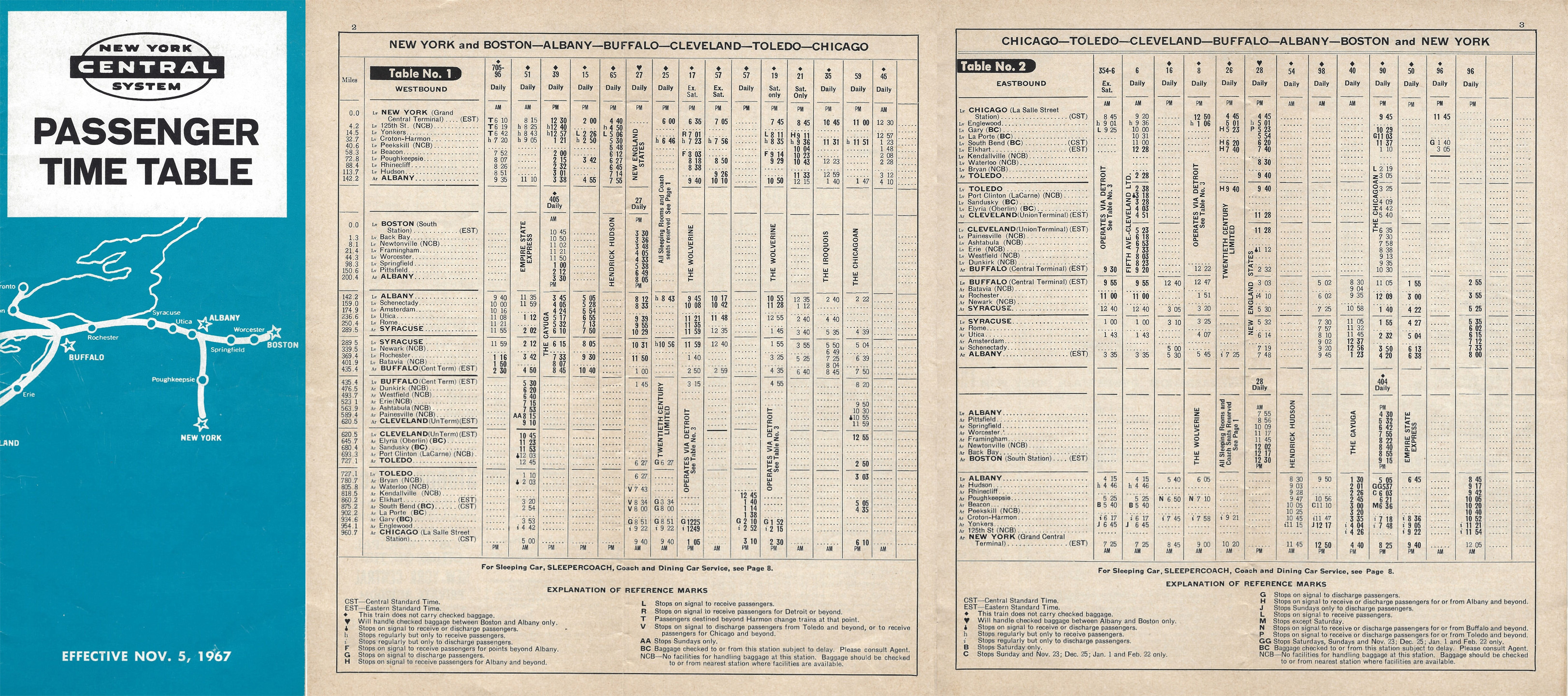

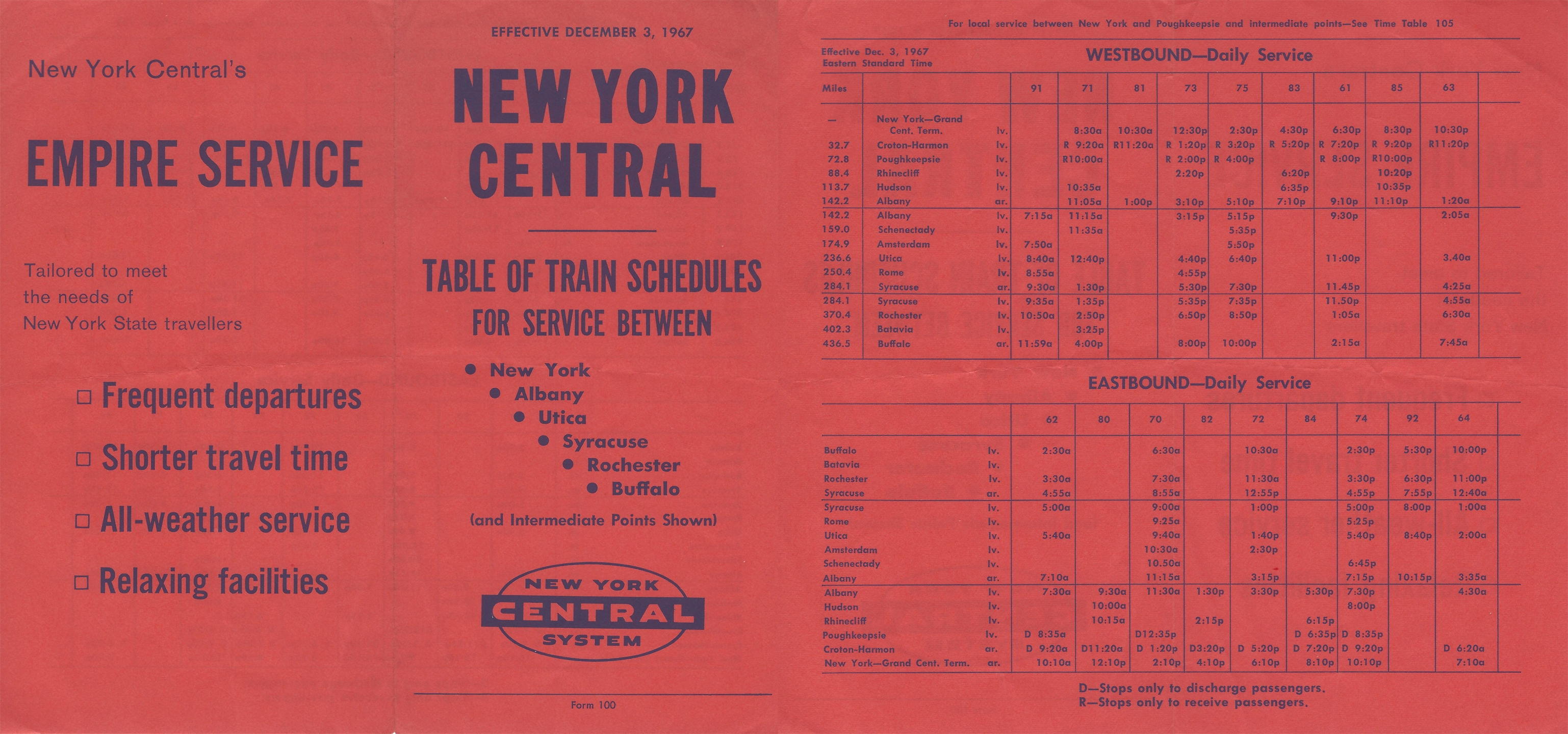

ABOVE: New York Central passenger timetable issued in November 1967 and BELOW the new December 1967 "Empire Service" timetable.

To the Central’s credit, considerable resources were expended to try and make the fledging “Empire Service” a success. A fleet of day coaches were specifically refurbished, along the modification of others into (new for the time) snack bar cars. On-board crews were re-trained in providing positive customer service and dispatchers were instructed to keep the short trains moving on schedule. Travel times were reduced by the elimination of lengthy stops to handle mail & express (a business which also was rapidly disappearing from the rails in favor of faster air or trucks). And a small-scale marketing newspaper and radio campaign was launched in the cities along the route.

The Central consolidated 11 daily local and long-distance trains out of New York City into eight round-trips New York-Albany, five round-trips New York-Buffalo, and one additional round-trip Albany-Buffalo. Three of the New York-Buffalo trains continued via connections at Buffalo Central Terminal west to Cleveland & Chicago, including the no name successor to the 20th Century Limited (predecessor to today’s Lake Shore Limited). In addition, two connecting trains operated west of Buffalo through Southern Ontario to Detroit and then onto Chicago through Michigan. And a daily overnight round-trip connection to Toronto was also provided.

Was the Central’s “Empire Service” experiment a success? Generally, yes! Marginal increases in ridership and revenues soon occurred, which when combined with the significantly reduced operating costs, at least got the remaining trains to near a break-even point in relatively short order. Robert D. Timpane, then the railroad's assistant vice president of operating administration oversaw a dedicated team of managment trainees monitoring the service quality and timekeeping. Monthly meetings between railroad operating officials, union representatives, and the Public Service Commission were held to evaluate and adjust the service.

Empire Service timetables from the New York Central through Penn Central to Amtrak.

Unfortunately, with the February 1, 1968 merger of the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad becoming the ill-fated Penn Central, the pro-passenger emphasis soon waned and service rapidly deteriorated, along with many of the passengers once again seeking other travel options. The Penn Central continued operating Empire Service up until the start of Amtrak on May 1, 1971; though for several subsequent years, Amtrak simply contracted with the Penn Central to run the service.

Still despite its early troubles the Empire Service was the start of something worthwhile and long lasting. On Monday December 4th, 2017 at the Albany-Rensselaer Rail Station, a two-hour ceremony was held to mark the half century of Empire Service. Attendees included representatives from Amtrak, State and local government, rail advocates and individuals who were (or who had family members were) involved in the creation of this intercity passenger rail service. Speeches were given, and a light lunch was served followed up by dessert, including a 50th Anniversary cake, complete with the 5oth anniversary variation of the current service logo.

The Empire Service 50th Anniversary cake served at the special cermony held at the Albany-Rensselaer Rail Station in Dec 4th, 2017.

A 1980s brochure from the New York State Department of Transportation on their sucessful Empire Corridor High Speed Rail Program, that was funded by the state goverment and completed in partnership with Amtrak.

Empire Service Under Amtrak & New York State

BIG GAINS in ridership would have to wait until after the Amtrak Era starting in May 1971. The first increase in ridership was due to the Energy Crisis of the 1970s, which made train travel became more attractive because of high gas prices at the pump. Ridership increased from 466,200 in 1973 to 652,600 in 1975 after the OPEC oil embargo following the Yom Kippur War.

This spurred renewed interest in “energy efficient” rail transportation and New York State embarked on a big investment in Amtrak’s “Empire Corridor”. Funded by several bond issues the state made a big investment of over $100 million in intercity passenger rail infrastructure from 1975 to 1991 as part of a Empire Corridor High Speed Rail Program. This work including upgrades and replacement of tracks, signaling, and stations. The infrastructure renewal program enabled a doubling of train frequencies and a slashing of travel times south of Albany from 3 hours to 2 hours 15 minutes hours by the early 1980s.

Amtrak at this time also introduced its French derived Rohr Turbliner gas turbine train-sets, giving the service a high-speed image as speeds increased to 110-mph in the Capital District. The introduction alone of new sleek modern trains is credited to boosting ridership overseas, what the British called the “nose-cone” effect after the mid-1970s introduction their streamlined high-speed Intercity 125 HST diesel train boosted ridership even were travel times remained the same!

The end result of this investment by the state and Amtrak was a doubling of ridership from 1975 to 1985 from about 700,000 to over 1.2 million annually. This not only confirmed the research and concepts developed by the passenger department of the New York Central, but followed results overseas where fast and frequent intercity service was similarly successful in the 1960 and 70s.

Ridership growth for the Empire Corridor during the ten year High Speed Rail Program of 1975-85, graphics from NYSDOT report.

Since the 1980s there have been few changes in the speed, frequency, and scheduling of the intercity rail service that exists now today in Upstate New York. The biggest change was the switch in 1991 from Grand Central Terminal to Penn Station as the Empire Corridor terminal in New York City. This occurred after the opening of the Empire Connection, a recondition former freight line to the West Side of Manhattan.

Service was also extended to Niagara Falls, Toronto, Montreal, and Rutland by extending existing Empire Service trains, some of which were renamed becoming the Maple Leave, Adirondack, and Ethan Allen Express. There have also been built several new stations including the CDTA Albany Rensselaer Rail Station which open in 2002 and is now Amtrak’s ninth-busiest station. New York-Albany is Amtrak’s busiest city-pair outside the Northeast Corridor.

The federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 led to a combined $942 million in federal and state money being invested into the Empire Corridor. This included the construction of a second mainline track between Albany and Schenectady, eliminating a major bottleneck in the system. Money was also invested in a forth platform track at the Rensselaer station, signaling work south of Albany, and new stations at Niagara Falls, Rochester, and now under construction in Schenectady. At Penn Station the West End Concourse was funded and built as “Phase One” of the Moynihan Station expansion project across 8th Ave in the Farley Post Office.

Today there are 13 Empire Corridor round-trips New York-Albany and 4 round-trips New York-Buffalo, including the Lake Shore Limited to Chicago. In FY 2016-17 the Empire Corridor saw 1.7 million passengers with 1.2 million of those New York-Albany. Since 1995 ridership has increased about 30% according to statistics provided by the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT).

In response to Section 209 of Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 the Empire Service joins the Adirondack and Ethan Allen as a fully state supported corridor train. As mandated by the federal law, NYSDOT in FY 2016-17 budgeting $44,330,000 in operating and capital support to Amtrak of intercity trains (excluding the Lake Shore Limited) in Upstate NY.

What the future holds for intercity service in Upstate New York is hard to say, but hopefully the Empire Service will continue to see further investment and development until by the 75th anniversary it reaches its logical conclusion as a fast, frequent, and reliable intercity “higher speed” service second to none in the nation.

BY Bruce B. Becker & Benjamin J. Turon

PRIMARY SOURCES: New York Central Headlight magazine January 1968; “In Lieu of the Great Steel Fleet: Central’s last bid for passengers” by Victor Hand in Trains Magazine, Nov. 1968; “New York State’s High Speed Empire Corridor” by Louis Rossi, NYSDOT 1985; "Twilight of the Great Trains" by Fred Frailey; "New York Central and the Trains of the Future" by Geoffrey H. Doughty; “Flight of the M-497” by Hank Morris and Don Wetzel; and “At 50, Empire Service has covered a lot of ground” by Eric Anderson for the Albany Times Union.

IMAGE CREDITS: Various Public Domain sources including the Library of Congress and the personal collections of Bruce Becker and Benjamin Turon