Corridor Service Development Plan

Corridor Service Development Plan

ABOVE: Traveling at around 100 MPH, the westbound Ethan Allen crosses Fuller Road in Albany NY.

Introduction

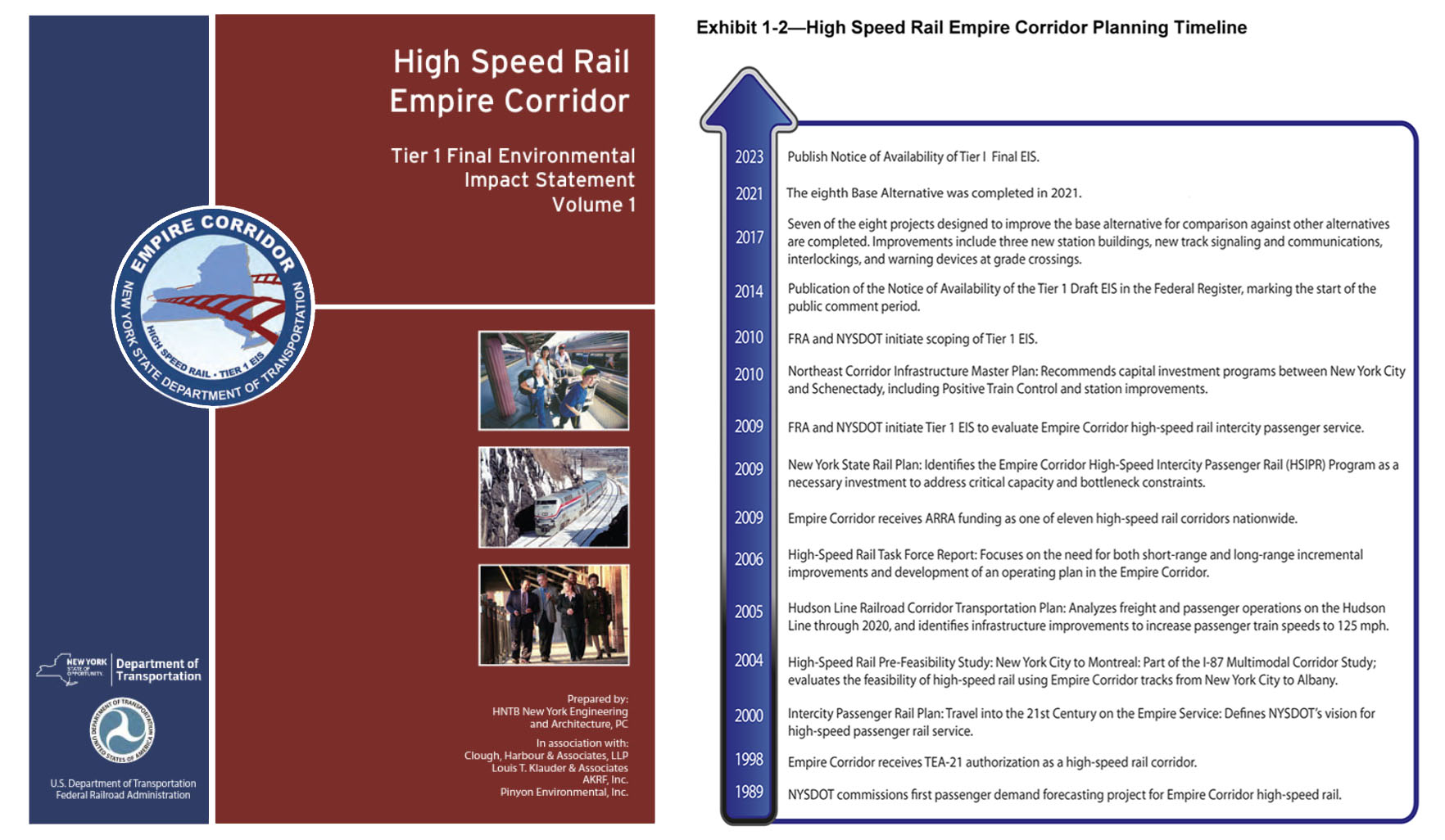

The Federal Railroad Adminstration signed the Empire Corridor Tier I Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) on February 2, 2023 – a Notice of Availability appeared in the Federal Register on February 17, 2023. With the receipt of a Record of Decision from the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) for the Empire Corridor Tier I Final Environmental Impact Statement, we now have the opportunity to begin the undertaking of the biggest transportation project in Upstate New York since the NYS Thruway in the 1950s.

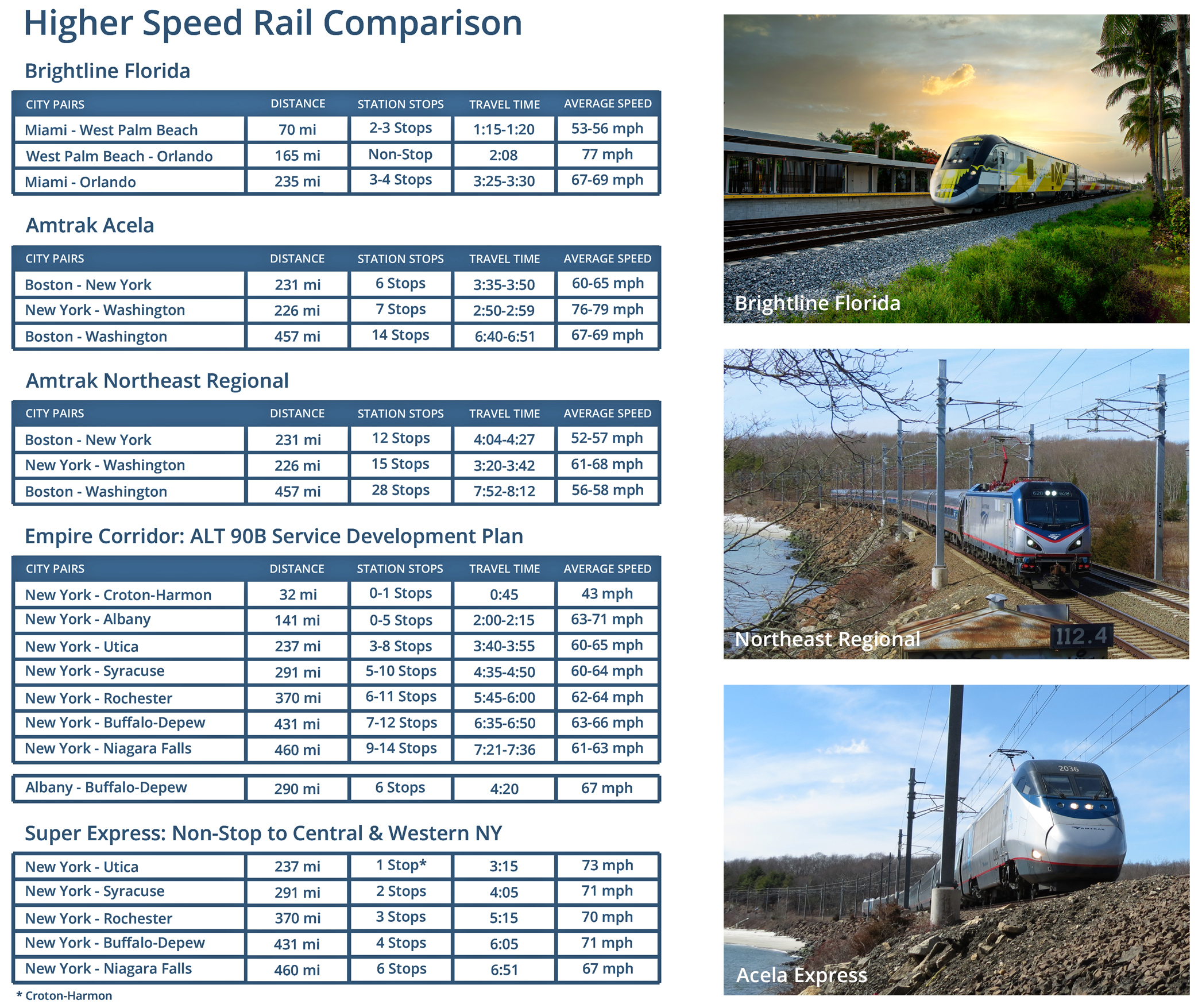

A modern intercity rail service connecting Upstate New York with New York City would boost the socio-economic prospects of cities big and small by offering a convenient and efficient transportation alternative, supplemental to existing air service and highways. A passenger rail service offering train frequencies and travel times equivalent to Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor and Brightline in Florida would be a catalyst for attracting further investment in the high tech, higher education, and tourist industries of Upstate New York.

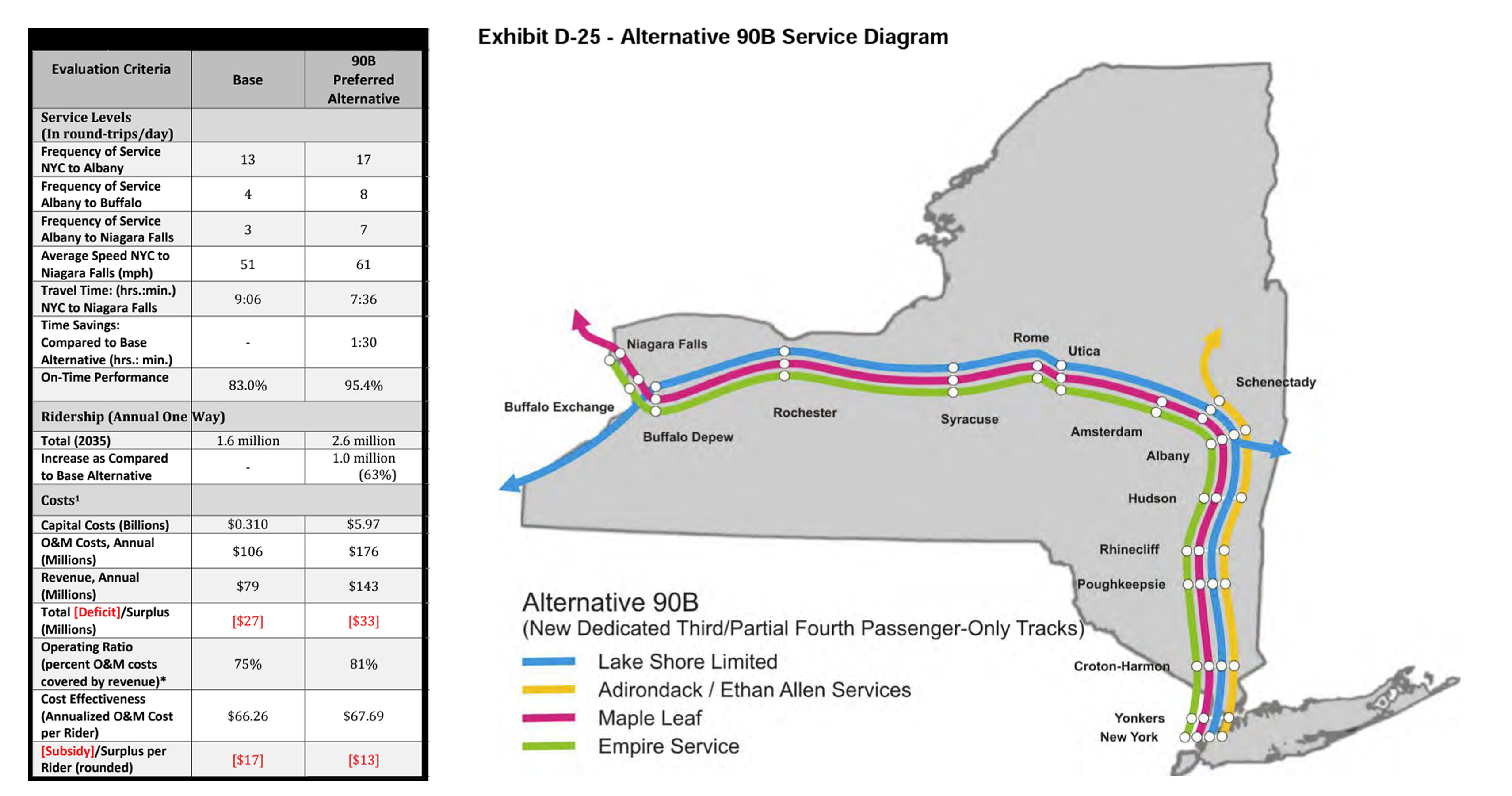

The Preferred Alterative 90B with its accompanying Service Development Plan offers a pragmatic path forward—by building a new “Dedicated Express Track” for intercity passenger trains within the existing historic railway right-of-way from the Capital District to the Niagara Frontier, building upon the past to create the future.

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Appendices

View and Download by Clicking on the Links Below...

Volume 1 – Final Environmental Impact Statement, which includes:

- Cover Sheet, Signature Page, Table of Contents, and Executive Summary

- Chapter 1 – Introduction and Purpose and Need

- Chapter 2 – Existing Transportation Conditions and Major Markets

- Chapter 3 – Alternatives

- Chapter 4 – Social, Economic, and Environmental Considerations

- Chapter 5 – Financial Capacity

- Chapter 6 – Comparison of Alternatives

- Chapter 7 – Comments and Coordination

- References

- Acronyms

- Glossary of Terms

- List of Preparers

Volume 2 – Appendix A

Volume 3 – Appendices B - H

- Appendix B – Ridership and Revenue Forecasting

- Appendix C – Alternatives Development and Screening Report

- Appendix D – Rail Network Operations Simulation

- Appendix E – Existing Transportation Conditions Supporting Documentation

- Appendix F – Capital, Operating and Maintenance Costs Estimating Methodology

- Appendix G – Environmental Inventory and Impact Assessment

- Appendix H – Service Development Plan (This section contains the most detailed program information)

Volume 4 – Appendices I - J

Volume 5 – Appendices K

Organizational Links

New York State DOT Empire Corridor

Federal Railroad Administration Empire Corridor Environmental Reviews

Making the Most of the Corridor ID Program

Express Track to the Future

Express Track to the Future

A sixty-page booklet reviewing the history, present, and potential future of the Empire Corridor – organized into short chapters with extensive photos and graphics – with a focus on the Service Development Plan of the Empire Corridor Tier I Final Environmental Impact Statement.

Available Online here as a PDF Booklet

ABOVE: The Albany-Rensselaer Rail Station is Amtrak's ninth-busiest station, the station being served by all Empire Corridor trains, including the Adirondack, Berkshire Flyer, Empire Service, Ethan Allen Express, Lake Shore Limited, and Maple Leaf. A fourth platform track and other track upgrades were undertaken last decaded, funded by grant money from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

The Empire Corridor Today

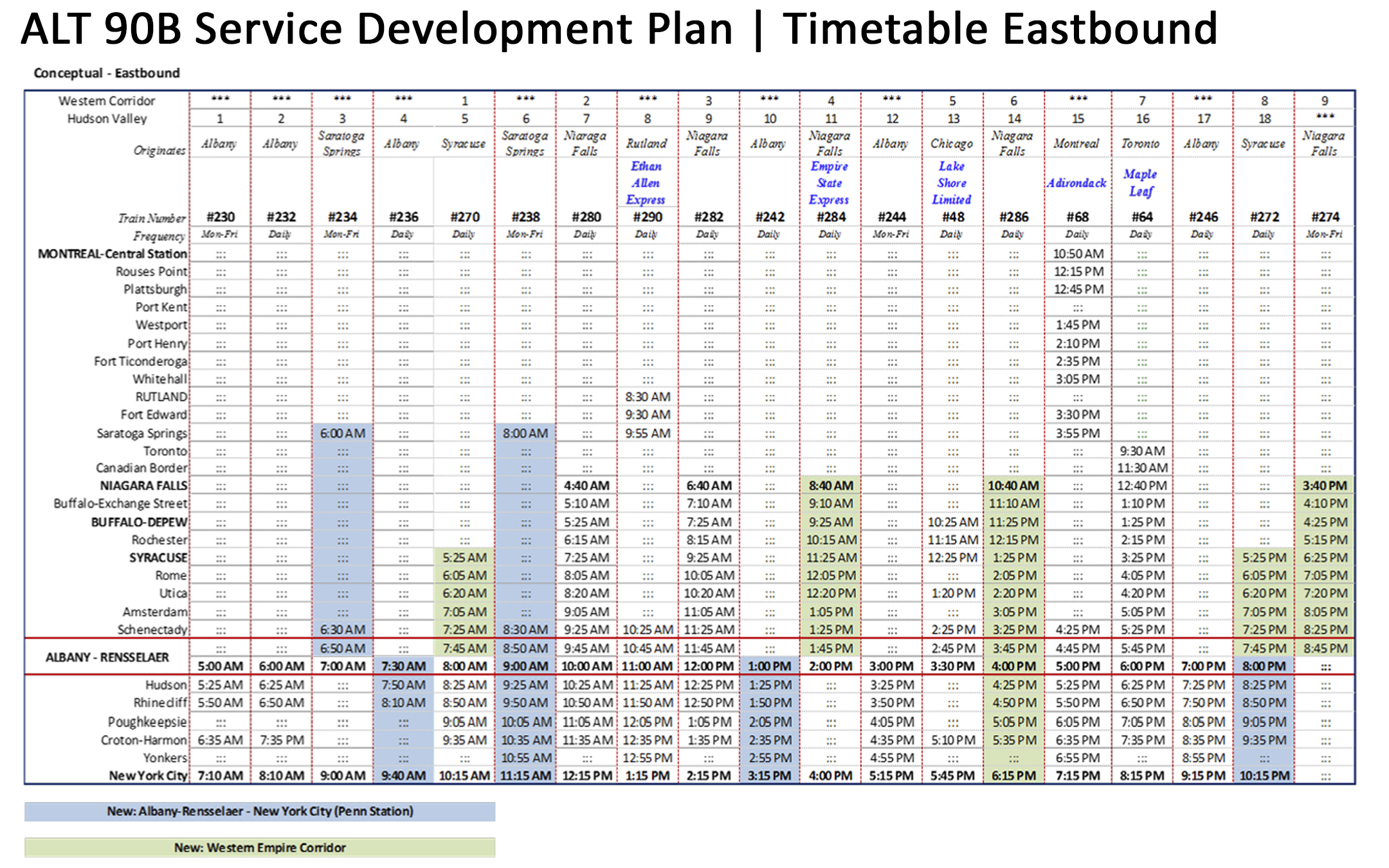

The Empire Corridor is a 461-mile intercity rail corridor stretching between New York City and Niagara Falls, serving the major population centers of the Hudson Valley, Capital District, Central New York, and Western New York. The corridor is operated by Amtrak, the national passenger railroad, with annual operating and capital support made by the State of New York through NYSDOT, the state’s department of transportation, which oversees the state-supported passenger rail service.

Under Section 209 of the federal Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (PRIIA) state financial support is mandated for all Amtrak services (non-NEC) under 750 miles. NYSDOT therefore contracts with Amtrak to operate the Empire Corridor—the exception being the long-distance New York-Boston-Chicago ‘Lake Shore Limited’ which is part of Amtrak’s ‘National System’. Before the pandemic in FY 2018-19 NYSDOT paid Amtrak $44.33 million for operating costs not covered by ticket sales, as well as capital investment in track and equipment.

The corridor today hosts thirteen roundtrips New York-Albany, with four that extend service to Buffalo, including the long-distance ‘Lake Shore Limited’ to Chicago and the ‘Maple Leaf’ to Toronto. Travel times between New York City and Albany are about 2h 30m, and eight hours to Buffalo. In FY 2023 the ridership of Empire Corridor services was 1.2 million New York-Albany, and over 452,000 Albany-Niagara Falls-Toronto.

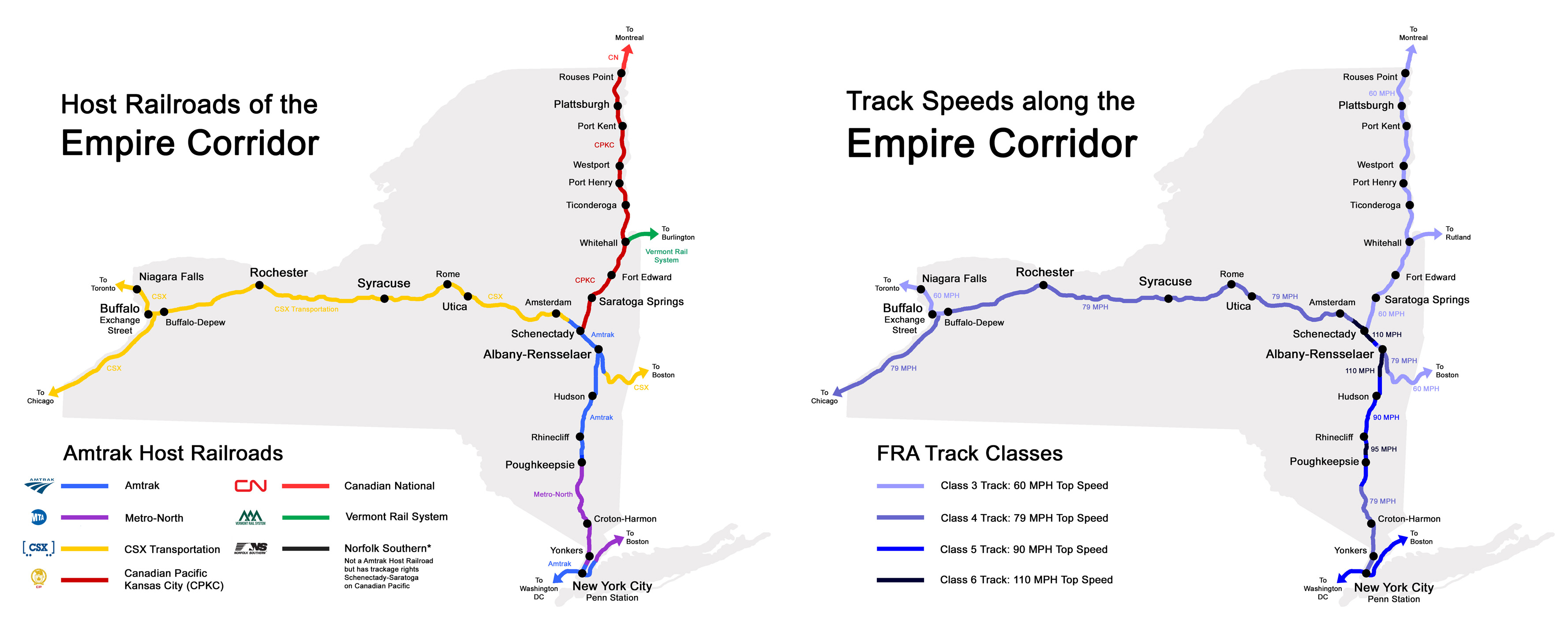

There are three “host railroads” for the Empire Corridor, with the Hudson Line divided between the commuter railroad Metro-North and Amtrak, and west of Schenectady (Hoffmans) the Class One freight railroad CSX Transportation. There is friction between Amtrak and the host railroads concerning the timekeeping. Legally since its creation, in return for relieving the private railroads of their intercity passenger rail public service obligations, the federal government mandated that passenger trains have priority over freight trains. However, in practice this has not always been true.

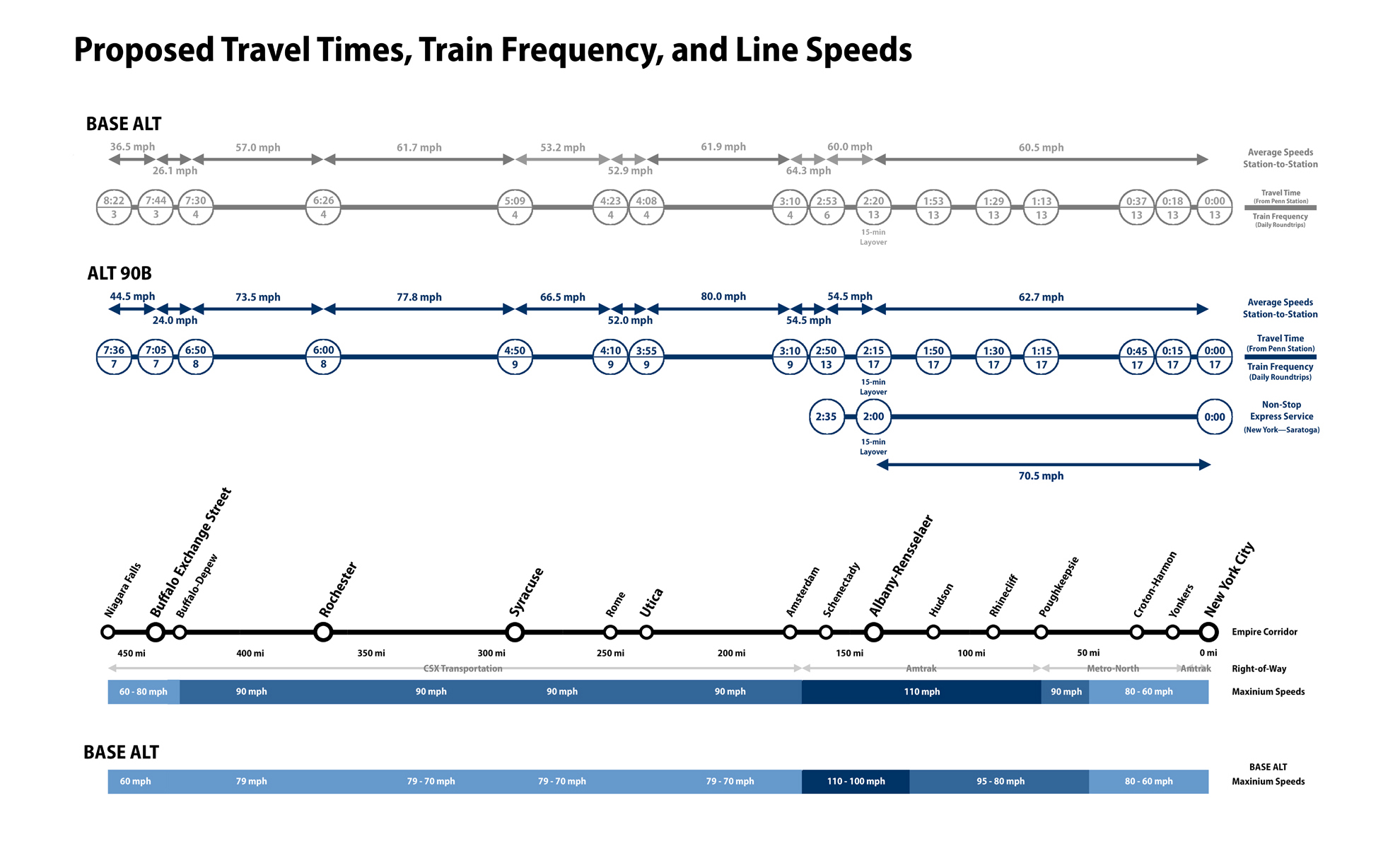

The top speed for Amtrak trains along the Empire Corridor is 110-mph on three sections of mainline through the Capital District on Amtrak tracks, with 90-mph south from Stuyvesant to Poughkeepsie. On Metro-North’s section of the Hudson Line south of Poughkeepsie speeds are 80 to 70-mph, with 60-mph on Amtrak’s Empire Connection from the Spuyten Duyvil Bridge south along the westside of Manhattan to Penn Station. West of Amsterdam the top speed on the CSX mainline to Buffalo is 79-mph, with 60-mph for the 28 miles of CSX’s Niagara Branch.

Empire Corridor | Host Railroads & Track Speeds Infographic PDF

ABOVE: A Empire Service train racing westbound at about 95 MPH in Glenville NY, west of Schenectady on Amtrak's Hudson Line. ALT 90B would extend 90MPH speeds west of the Capital District to Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo on new dedicated "express tracks" for passenger trains.

The Tier One EIS

The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) signed off on the Tier I Final Environ-mental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the Empire Corridor on February 2, 2023 – the Notice of Availability appearing in the Federal Register on February 17, 2023. It had been a long process, taking over 15 years and 4 months*, starting in 2009 with the issuance of a notice of intent to prepare an environmental impact study, with the Draft EIS released for public comments and several open house hearings in Spring 2014.

Why so long? In part the delay came from a dispute between New York State and CSX, the Class One freight railroad that had acquired half of the Conrail system in 1999 in a joint deal with rival freight railroad Norfolk Southern. CSX acquired the ex-New York Central lines in Upstate NY, including the Empire Corridor. CSX has a 90-mph maximum speed limit for its rail lines, and at the start of the EIS process CSX and NYSDOT signed an agreement to that fact in 2010, following the example of other states like Virginia that wish to upgrade their state supported Amtrak services.

However, the powers that be in Albany pushed for 110-mph as the top speed on the CSX right-of-way, and despite the agreement from 2010, pushed CSX to relent, which it refused to do, rallying its shippers in opposition. In its caustic official comments to the Draft EIS, the freight railroad listed every conceivable reason why high-speed trains on its tracks were a horrible idea, suggesting that the public fly or take the bus instead.

Eventually it seems that New York State relented, and Alterative 90B was chosen over Alterative 110 as the preferred alternative to develop into a Service Development Plan. Two “Very High-Speed Rail” alternatives with top speeds of 160 and 220-mph were rejected early during the Draft EIS process as too expensive. A 125-mph alterative (ALT 125) with new tracks on new right-of-way west of Albany was included in the Draft EIS, along with a 90-mph alterative (ALT 90A) on the existing double-track CSX mainline, as opposed to the proposed dedicated third track of ALT 90B and ALT 110.

Despite the ineptitude on the part of NYSDOT in completing the Final EIS in a timely manner, the preferred Alterative 90B is a sound plan, a credit to the state employees and consultants who prepared the EIS study. The installation of additional third and fourth “express tracks” dedicated to passenger trains would add capacity and provide the ability to route passenger trains around freight trains, while operating at higher speeds.

ABOVE: The public workshop at the Albany NanoTech Complex for the Empire Corridor Draft EIS in March 2014.

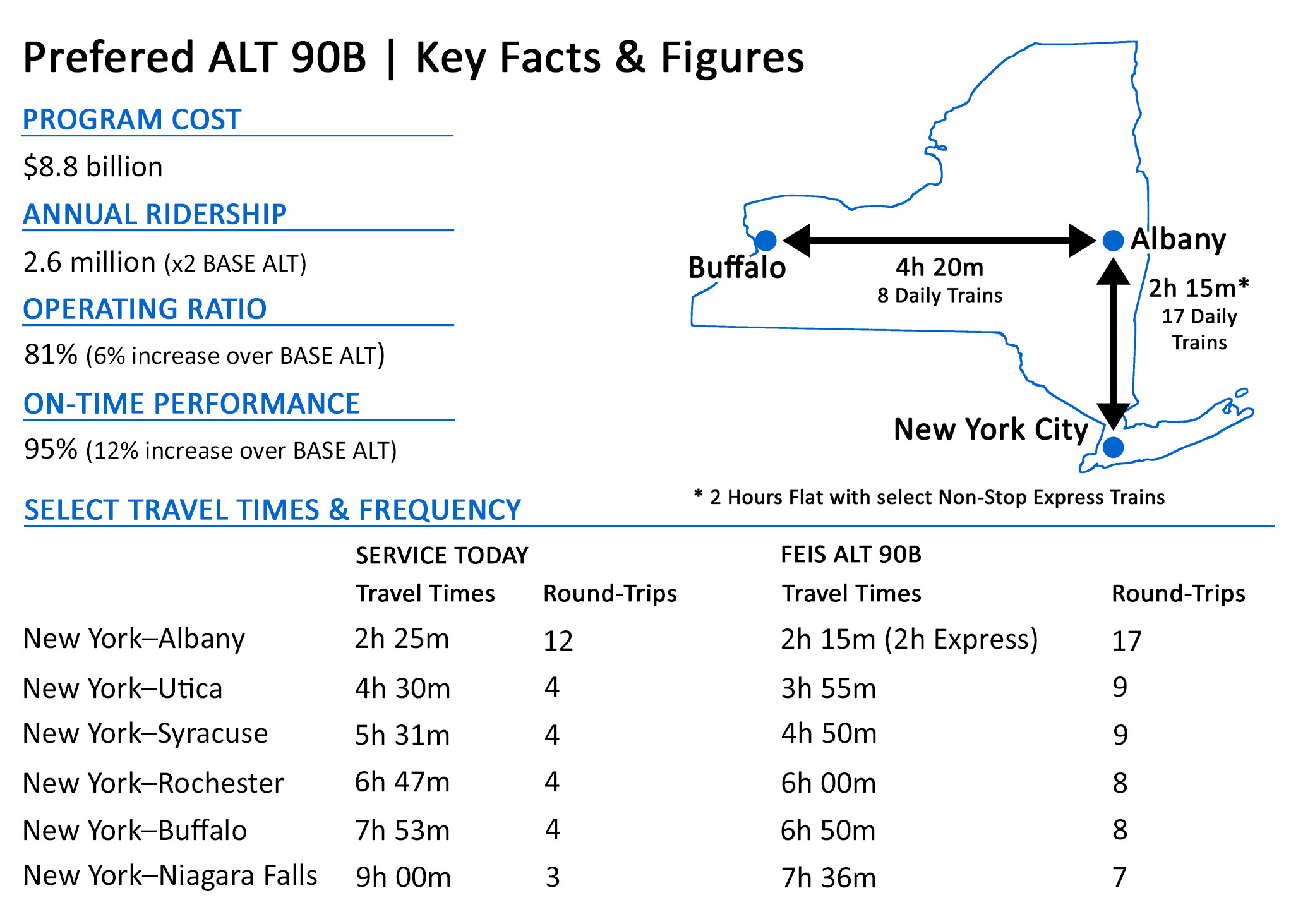

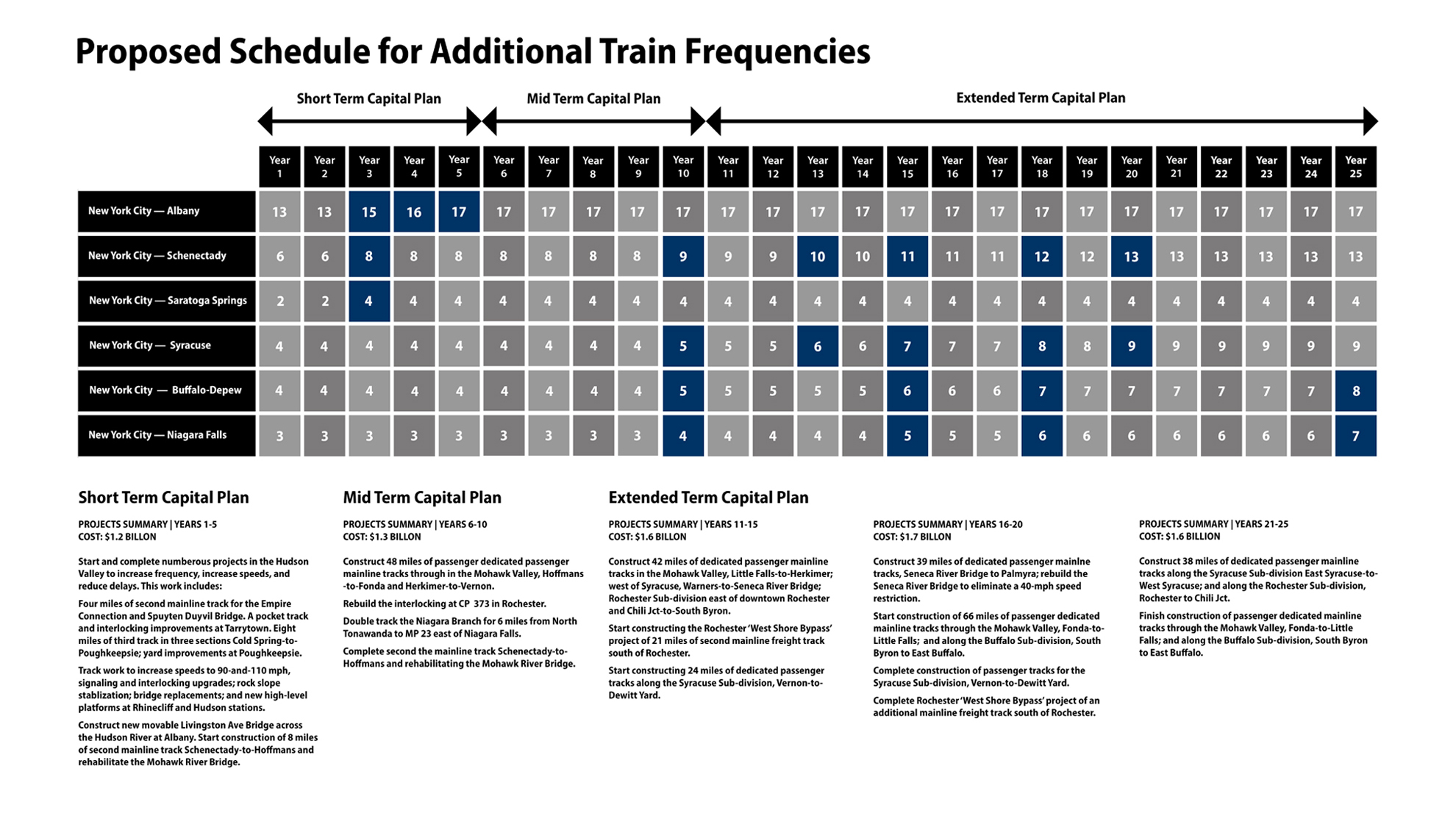

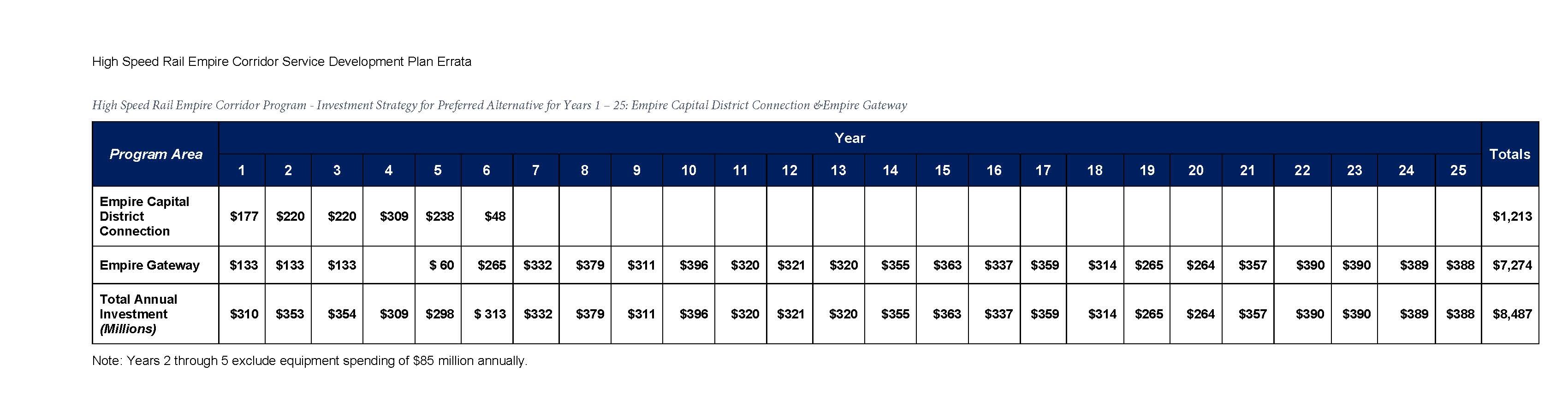

Alternative 90B, would result in a 1½ hour savings in travel time and a 10 mph faster top speed over the Base Alterative, with four additional roundtrips west of Albany to Buffalo, for a total of eight roundtrips, with a 95% on-time performance. Minutes-delayed and trip times for CSX freight between the Selkirk Yard south of Albany to Buffalo would be reduced as well. The current project cost is estimated at $8.8 billion over 25 years, with approximately $240 - $250 million annually. Future costs will vary due to inflation and changes to the Service Development Plan. Annual ridership is estimated at 2.6 million, a million more than the Base Alterative, with an 81% operating ratio, 6% higher than the Base Alterative.

Compared to Alterative 90B, Alternative 110 was seen as having significantly higher costs and greater potential for environmental impacts than Alternative 90B because of the required property acquisition, while only achieving a modest improvement in overall performance. Left unwritten was host railroad CSX’s opposition to 110-mph speeds on or adjacent to its right-of-way. Alternative 125 with a cost of nearly $16 billion was rejected as being too expensive, while taking too long to confer benefits due to the time required to assemble, acquire, and construct a new right-of-way. In contrast, service would be incrementally improved as Alterative 90B was built out project by project, the first additional frequencies west of Albany coming at the ten-year mark.

The Final Tier I EIS includes a Service Development Plan with the schedule for implementation of the Preferred Alternative, to guide the 25 years of continued investment till project completion. The SDP outlines in detail a program of major infrastructure construction, and includes how the resulting new passenger service will be operated, equipment requirements, funding needs, and management systems. The Service Development Plan is being updated by NYSDOT with a $500,000 federal grant as of 2024, due to the length of time of competing the SDP, with key cost estimates in the report dating to 2017.

ALT 90B | Key Facts & Figures Infographic Flyer

ABOVE: An infographic showing the transformation of intercity passenger rail service along the Empire Corridor in terms of speed and frequency, contrasting current service with that proposed by the Service Development Plan of ALT 90B.

ABOVE: An infographic showing the planned implementation of ALT 90B under the Service Development Plan, including the addition of additional train frequencies. NYSDOT is working on an update of the Service Development Plan, that will hopefully speed up implementation.

NYSDOT Empire Corridor Rail Development Plan Infographics PDF

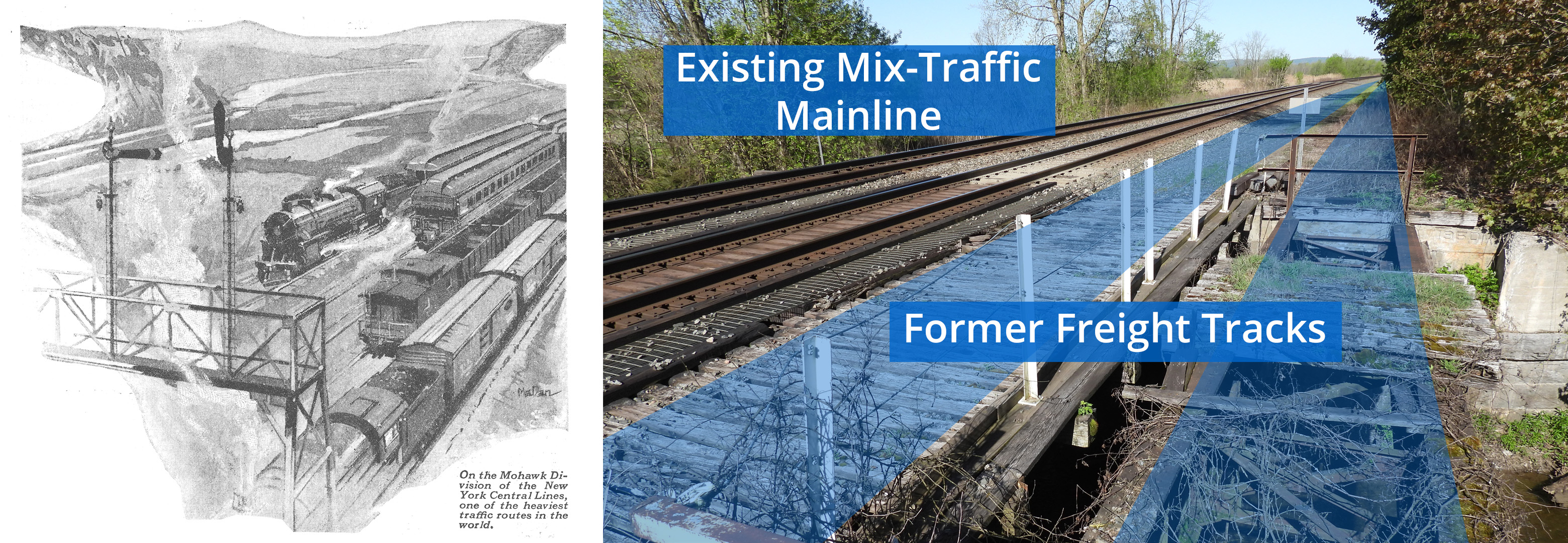

ABOVE: The type of civil engineering work called for in ALT 90B, constructing 370 miles of passenger dedicated 90 MPH third and fourth track along the existing CSX mainline from Schenectady to Buffalo, has already been undertaken by NYSDOT and Amtrak on a far smaller scale last decade during the construction of a second mainline track for approximately 18 miles between Albany and Schenectady, the project funded by high-speed rail grant from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

NYSDOT | Albany-Schenectady Second Main Track Website

ABOVE: The rail bridge over Danascara Creek in Tribes Hill at Milepost 183, west of Amsterdam on the CSX mainline. Bridges like this one, built in 1950 when the New York Central mainline was still four tracks – the two tracks on the southside dedicated to passenger trains and the two tracks on the northside dedicated to freight trains – will have to be rebuilt or replaced to bring the entire infrastructure up to a state of good repair, while providing for the new third (and fourth) dedicated passenger track. The sharp curve just east of this location would be realigned to increase line speeds from the current 50-mph to 70-mph, one of the few locations (the curve at Little Falls another) where passenger train speeds would fall below 90-mph.

New York Central Railroad | Wikipedia

ABOVE: A rendering from NYSDOT on the right of the new Livingston Ave Bridge (LAB) from the Albany side, on the left a photo the approach of the existing bridge. The new lift bridge would be built south of the existing swing bridge and incorporate a new recreational pathway for pedestrians and cyclists. Passenger train speeds will rise from 15 to 30-mph over the new span (the curving track at each end having an existing 40-mph speed limit) with two trains allowed to cross simultaneously.

NYSDOT | Livingston Avenue Bridge Project Website

ABOVE: The heavy steel rails of the Hudson Line alongside the Hudson River south of Albany, where 110 MPH speeds would be extented south to Poughkeepsie under the Service Development Plan of ALT 90B.

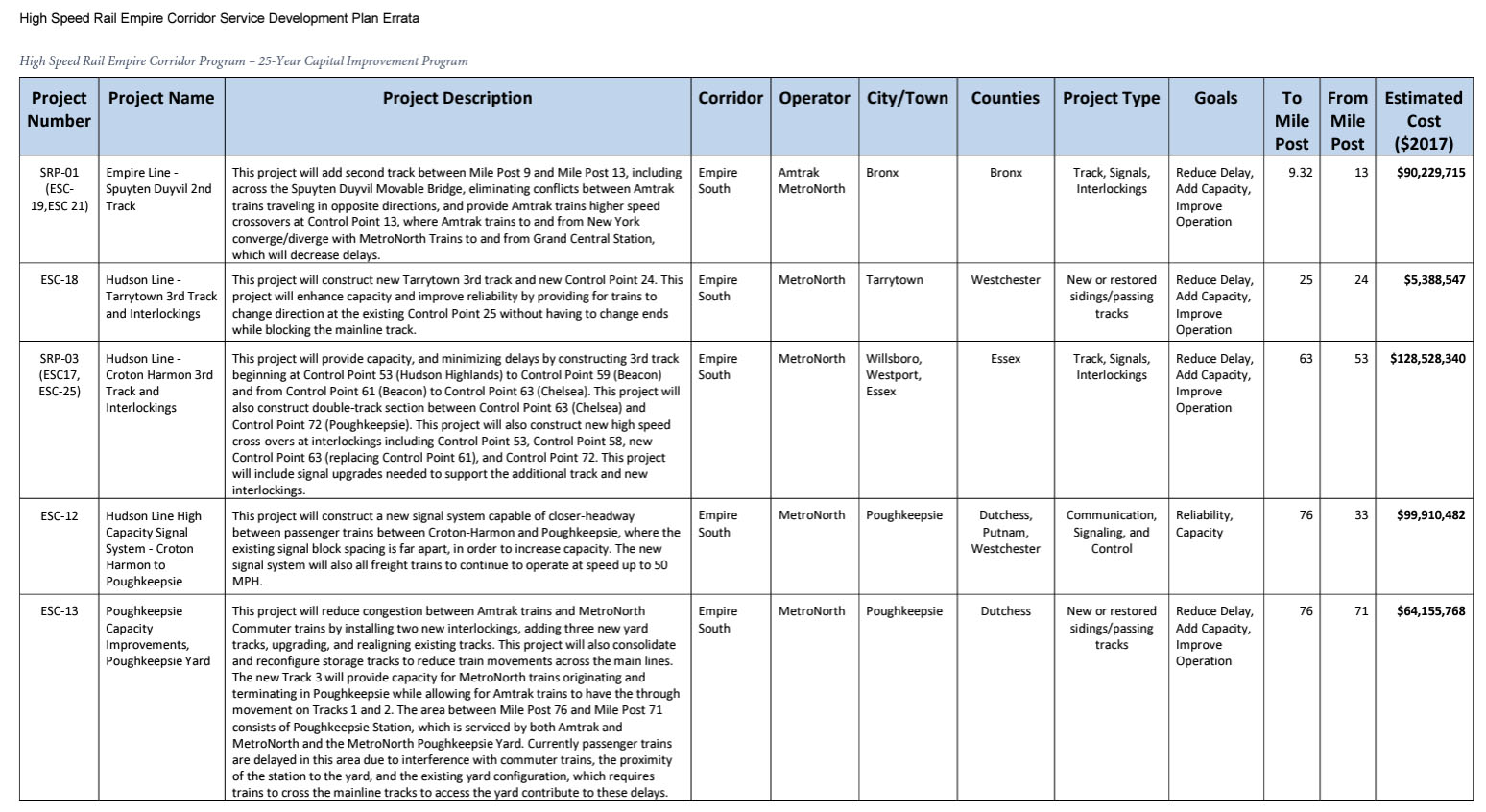

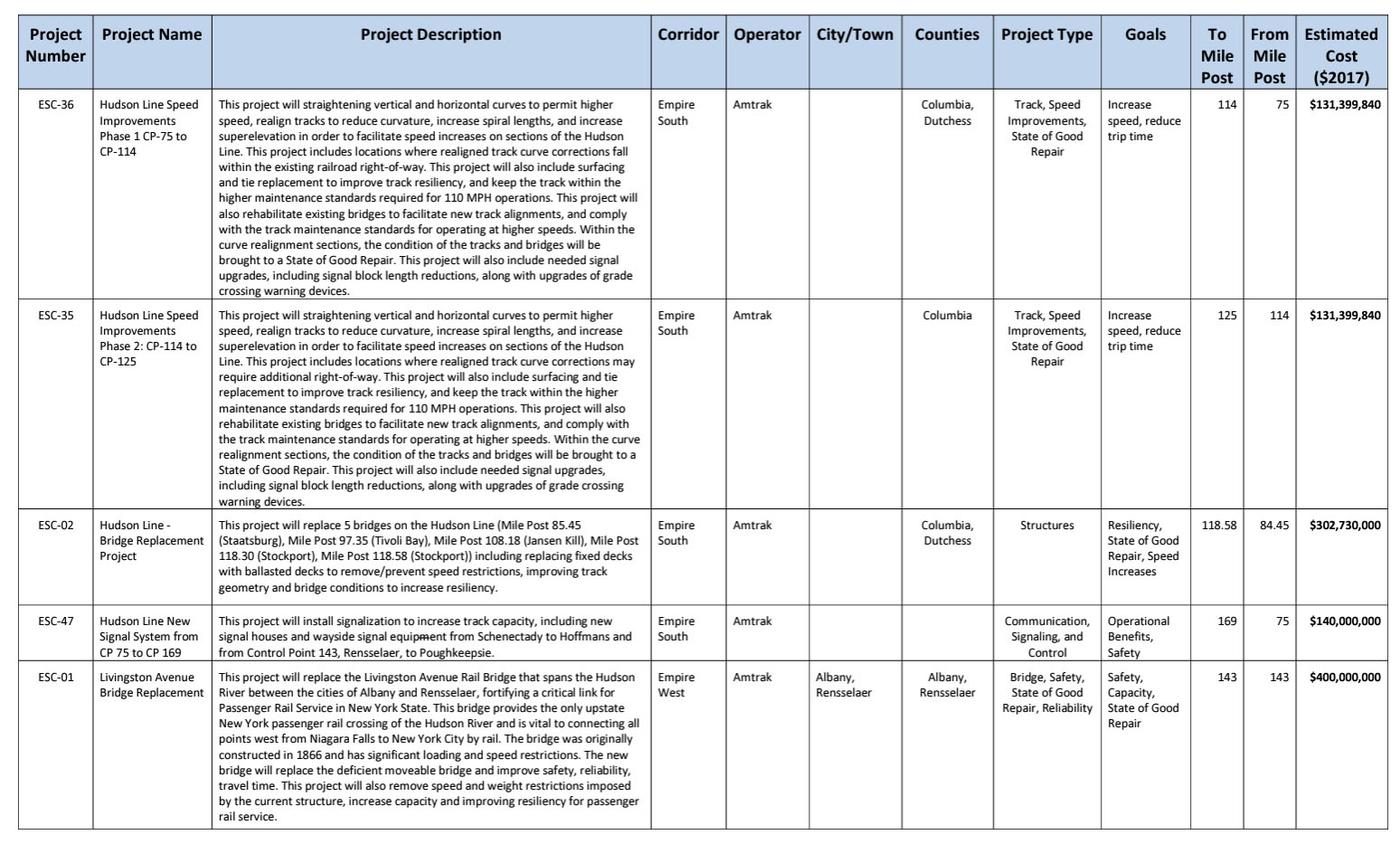

Empire South

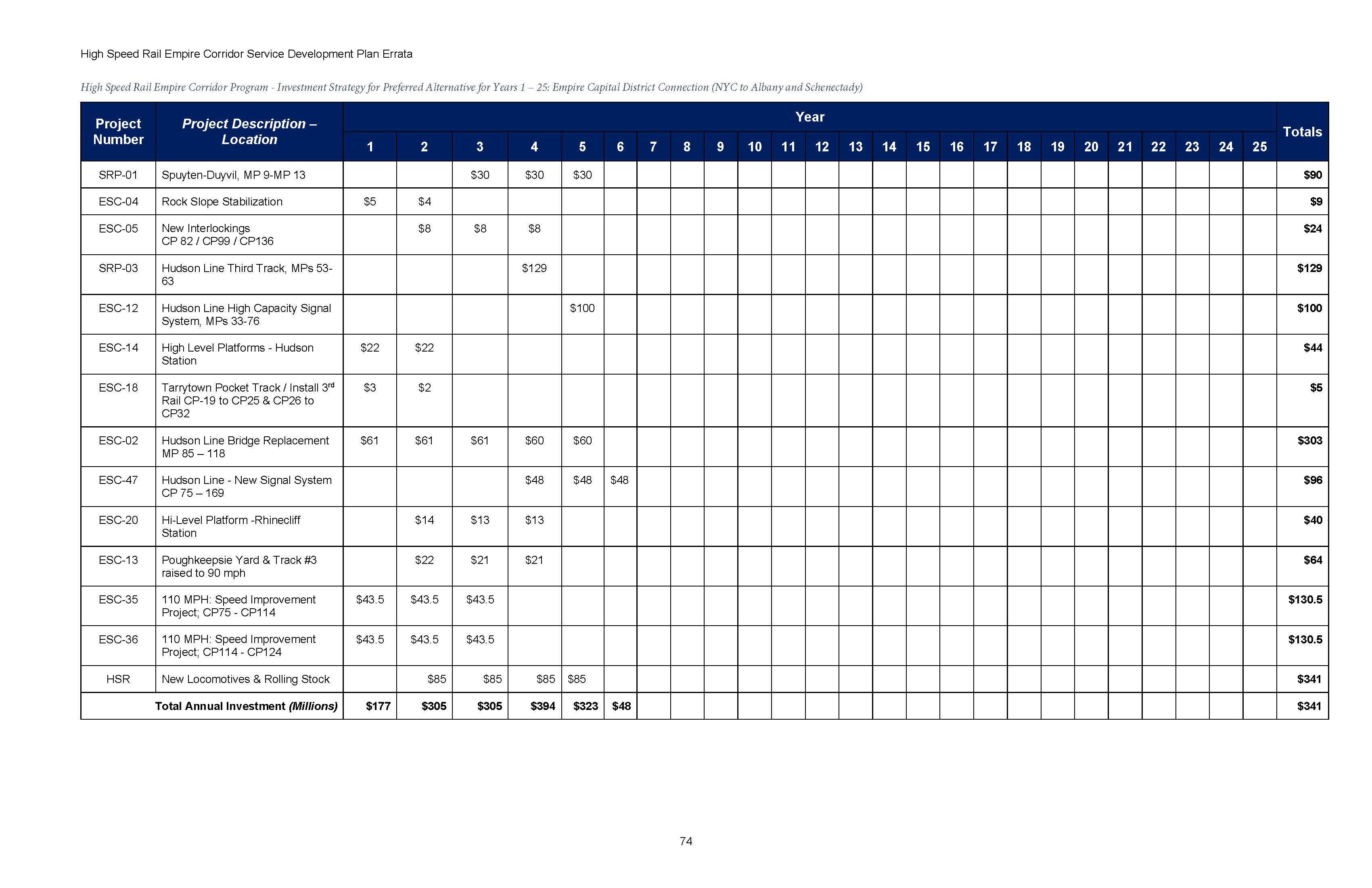

On the Empire Corridor South between New York City and Albany-Rensselaer, Alternative 90B includes the majority of the projects that were compiled in the Hudson Line Railroad Corridor Transportation Plan of 2005. These improvement projects were identified and agreed upon by the joint-users of the railway, including Amtrak, Metro-North, CSX, and Canadian Pacific (now CPKC), with NYSDOT included as a major stakeholder.

These civil engineering projects will together improve reliability, increase frequency, and reduced travel times for Amtrak service. They include: a second track on the Empire Connection, two sections of third track south of Poughkeepsie and yard improvements at Poughkeepsie, signaling and interlocking upgrades, rock slope stabilization, bridge replacements, track work to increase speeds to 90 and 110-mph, and new high-level platforms at the Rhinecliff and Hudson stations.

Constructing a new movable Livingston Ave Bridge across the Hudson River between Albany and Rensselaer is the biggest project, at an estimated $400 million. The existing railroad bridge has stone piers dating from the 1860s and a steel superstructure from the early 1900s. Its deteriorated state limits trains to crossing to one at a time at 15-mph, while troubles operating the swing bridge can delay both rail and maritime traffic. A new lift-type bridge would bring the crossing up to modern rail standards, include a new recreational walkway, while reliably accommodating waterborne on the river.

Travel times for intercity trains making all current intermediate station-stops between Penn Station and Rensselaer—Yonkers, Croton-Harmon, Poughkeepsie, Rhinecliff, and Hudson—would be reduced to 2hrs 15mins, a savings of 15 minutes over current schedules. A two-hour express service is proposed for certain train frequencies, the Service Development Plan stating that the “two-hour threshold is an important perceptual consideration in attracting travelers to this line.” Indeed, this was the goal of the failed High-Speed Rail program of the Pataki Administration, utilizing rebuilt Rohr Turboliners on upgraded tracks.

Average speed for the non-stop express would be over 70-mph for the 141 miles, and given that the travel time on busy section south of Croton-Harmon would remain 40-45 minutes, as Amtrak trains are slotted into the busy commuter traffic of Metro-North, the average speed from Croton-Harmon to Rensselaer would be over 80-mph. While not “true” high-speed rail, it would be one of fastest intercity rail services in the nation.

ABOVE: The CSX mainline with its broad former four-track right-of-way at “Big Nose” along the Mohawk River west of Fonda NY.

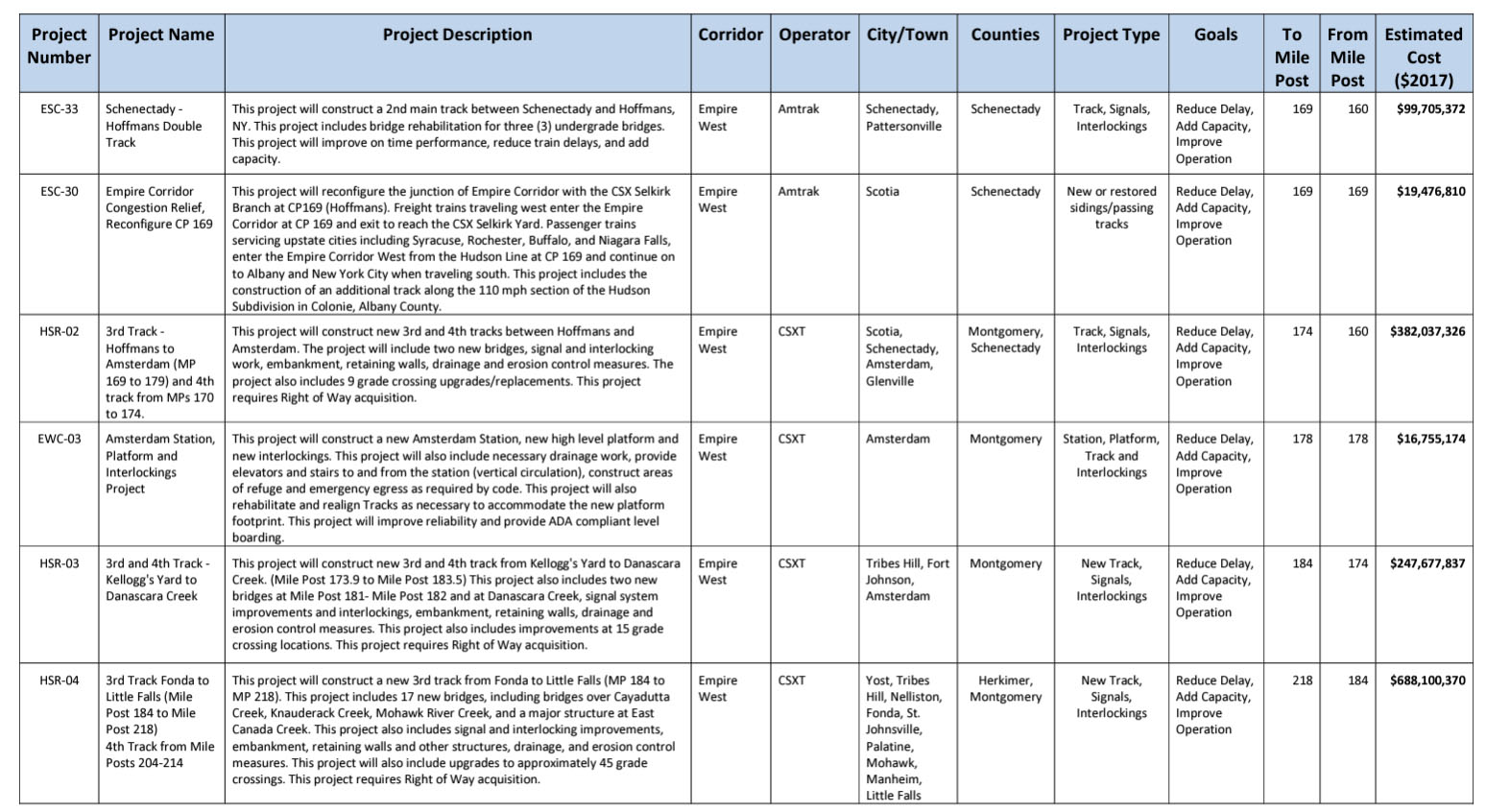

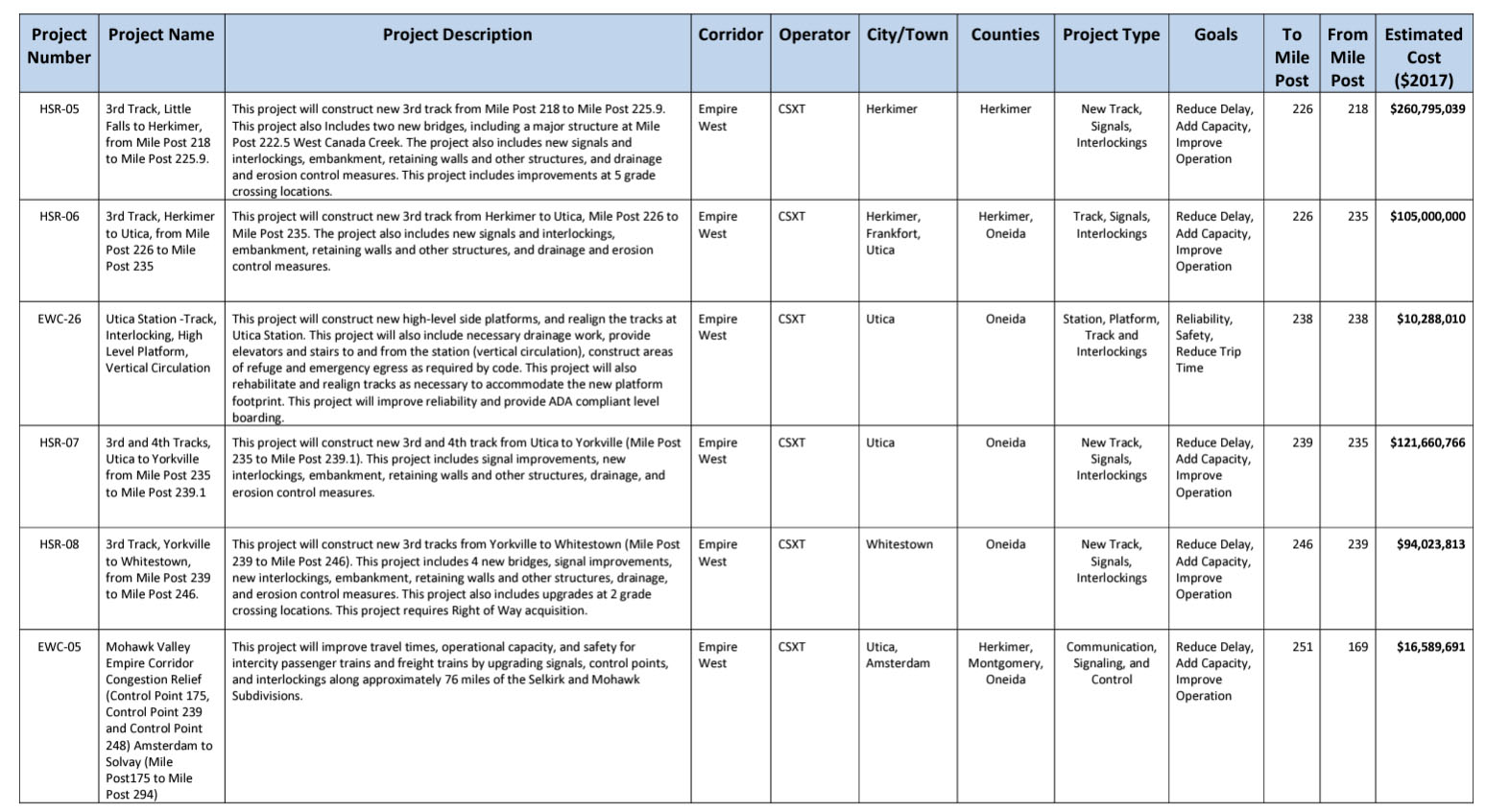

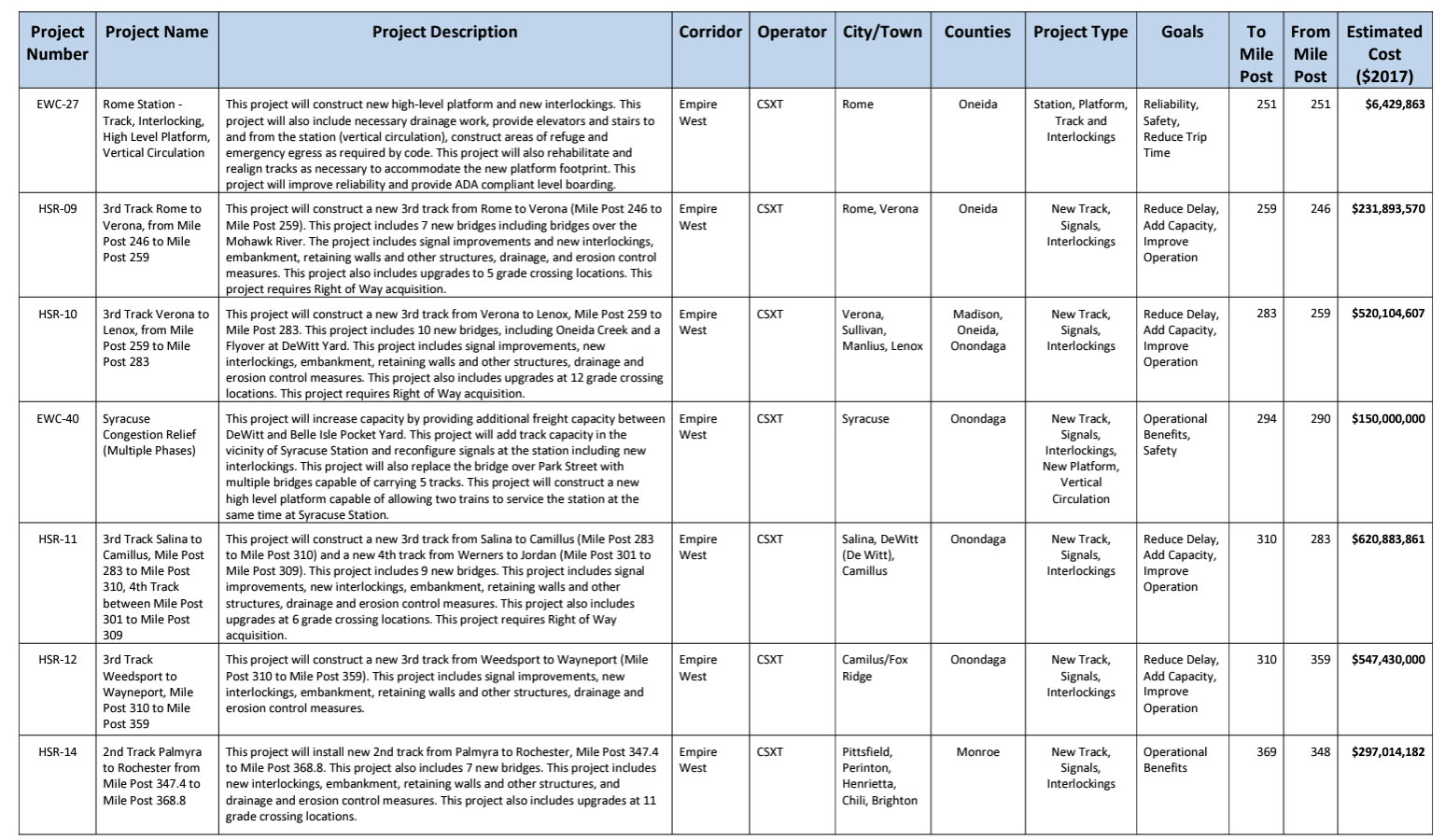

Empire West

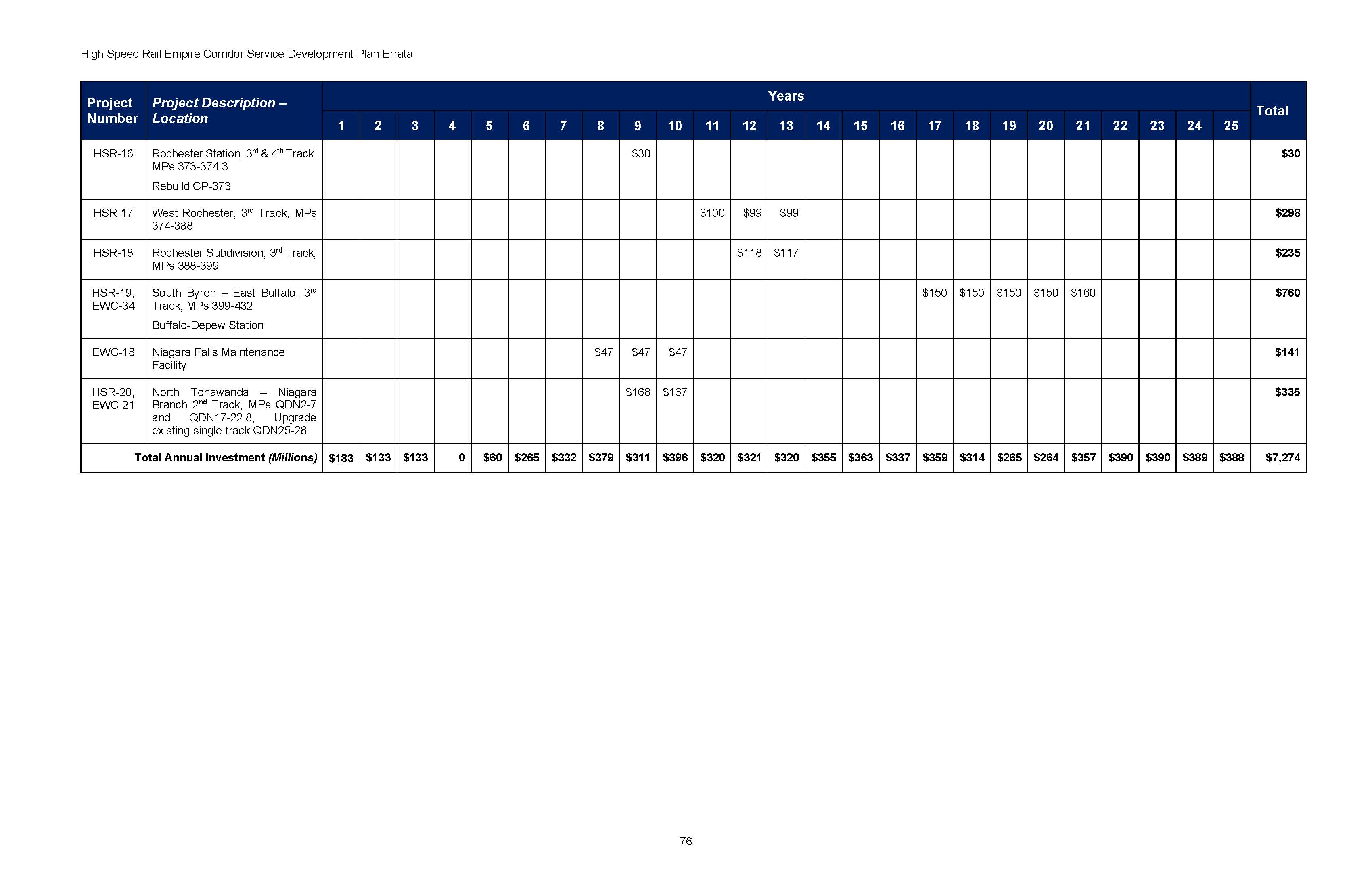

The primary focus of the Tier I EIS is on improving intercity passenger rail service west of Albany to Niagara Falls, as this section of the Empire Corridor has Amtrak service of a far lower intensity compared to the already relatively high-intensity service (for North America) down the Hudson Valley, from Rensselaer to Penn Station.

The Preferred Alterative 90B addresses the inequalities in service levels by solving the primary issue preventing faster and more frequent passenger service, the shared-used of a busy double track mainline—controlled by freight railroad CSX Transportation—that hosts frequent but slower freight trains with the currently infrequent yet faster passenger trains. This mix of traffic is analogous to a two-lane highway full of heavy trucks and passenger cars, and the solution is equivalent to an express lane on an urban superhighway, a new ninety-mile-per-hour “express track” dedicated to passenger trains. This separation of freight and passenger rail traffic, would greatly improve the flow of traffic for both Amtrak and CSX, while increasing the capacity for more trains.

Alternative 90B would add a total of approximately 370 miles of additional trackage to segregate passenger rail and freight trains, essentially constituting a parallel railway to the existing double-track mainline. There would be a third dedicated passenger track for approximately 273 miles between Schenectady (MP 159) and Buffalo-Depew (MP 432), and an additional fourth passenger track for approximately 39 miles in five separate sections, allowing for the passing at speed of opposing passenger trains.

The design strategy of Alterative 90B has been coined by Spanish academics from the University at Cantabrai as “Alternate Double-Single Track” or a “ADST” line, which reduces construction costs by utilizing primarily single track, including through expensive segments with cuttings, embankments, tunnels, viaducts, and bridges, while utilizing double track primarily in cheaper build segments of favorable topography and only where it is necessary, to accommodate passing trains.

Several high-speed lines in Spain and one in Sweden have been built as ADST lines. In the USA the newly open Miami-Orlando ‘Brightline Florida’ has a few single-track segments, and the now under construction ‘Brightline West’ between Las Vegas and the Inland Empire will be primarily single-track, with like Alterative 90B, several long segments of double-track to allow for opposing trains to pass at speed. ADST works for less intensively trafficked passenger railways where a timetable of regular interval trains can be scheduled to have trains meet on the double-track sections. Because of this the proposed Empire Corridor timetables in the Service Development Plan are built in part around the planned sections of new third and fourth dedicated passenger tracks.

ABOVE: An ‘Empire Service’ train racing westward at 90 MPH in Glenville, NY on Amtrak tracks, ALT 90B would extend 90 MPH speeds about two hundred miles from Schenectady County to Erie County.

The maximum authorized speed on these new dedicated passenger tracks would be 90-mph, with high-speed No. 32.7 turnouts (switches) allowing for diverging moves of 80-mph at the interlockings (the complex of turnouts at a control point) so that a passenger train entering a segment of fourth track to pass an oncoming passenger train would only have to reduced speed by 10-mph, from 90 to 80-mph.

The top speed is set by host railroad CSX, which has a non-negotiable 90-mph speed limit on its right-of-way, which other states have accepted. This includes Virginia, which is undertaking building third and fourth dedicated passenger tracks with a 90-mph speed on the CSX mainline between Washington DC and Richmond VA. The other speed limit is federal regulations, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has limited speeds on lines with grade crossings to 110-mph. For speeds above 110-mph, full grade separation is required to create a “sealed corridor” with no grade crossings.

The new passenger dedicated, third mainline track, would primarily occupy the northern portion of the existing railbed that historically contained the two freight tracks of the former four-track mainline. The third track would be spaced with a 15-foot track center from the existing Track 2, the segments of fourth track having a 15-foot track center from the third track.

While a primary benefit of Alterative 90B is the minimum need for acquiring land outside the existing rail right-of-way, some land acquisition and roadway relocation would be required to expand the right-of-way to accommodate the fourth track segments and curve re-alignments for higher speeds. There would also be new segments of double track installed on the Niagara Branch (CSX) in Buffalo.

ABOVE: A photo progression illustrating how the new third and fourth dedicated passenger tracks will utilize the surplus right-of-way north of the existing double-track mainline. Location is Lock E10 on the Mohawk River east of Amsterdam NY.

Additional infrastructure would include three grade separated flyovers—one east of the Dewitt Yard east of Syracuse (MP 279); another to the east of the Rochester Yard (MP 366), and one east of the Buffalo-Depew Station (MP 427)—where the third track would pass over the two existing freight tracks on an elevated structure, avoiding freight yards located on the northside of the mainline and to reach existing stations located on the southside of the mainline. While capital intensive, the Service Development Plan sees the flyovers as worth the cost in minimizing interference between freight and passenger traffic that could lead to delays and longer travel times.

A new signal system to support the 90-mph line speeds would be installed and grade crossings rebuilt. All supporting physical infrastructure, including bridges and culverts, would be brought up to a good state of repair or replaced. The Service Development Plan states that the most efficient approach to rail infrastructure upgrades on such a heavily used railway as the CSX mainline is to visit each repair location only once, and to upgrade to a state of good repair all infrastructure elements at that location, even if some repairs or upgrades are not directly related to the program objectives.

Major station improvements would also have to be undertaken, to be fully compliant with the infrastructure and service levels laid out in the Service Development Plan. Amsterdam would get a new station with a downtown location (planning is currently underway) featuring an ADA-compliant high-level island platform—enabling the seamless level boarding of trains, greatly improving accessibility for those with mobility impairments—served by the new third and fourth passenger tracks. A new station building would be connected to the platform with an overhead concourse containing stairs and elevators.

Utica Union Station would see a new high-level platform built on the footprint of the existing side platform that serves Amtrak on mainline Track 1 and the scenic heritage Adirondack Railroad on a sidetrack. The existing mainline track would be shifted south to allow the island platform to be served by the new third and fourth passenger tracks, likely requiring an additional new platform and overhead pedestrian bridge to be built to serve the tourist excursion trains of the Adirondack Railroad. Rome would see a new high-level platform, stairs, and elevators built to serve the new third track.

ABOVE: The historic Utica Union Station would see major upgrades to tracks and platforms.

The Syracuse Station (William F. Walsh Regional Transportation Center) would see major work with new third and fourth passenger tracks serving a rebuilt high-level platform. This project would also replace the existing bridge over Park Street with a new bridge capable of carrying five tracks, while adding and upgrading interlockings and signaling to smooth the flow of freight and passenger trains. Amtrak trains will have to cross over the freight tracks of CSX from the southside of the right-of-way where the station is located to the northside where the dedicated third (and some segments of fourth) passenger tracks will run west to Rochester.

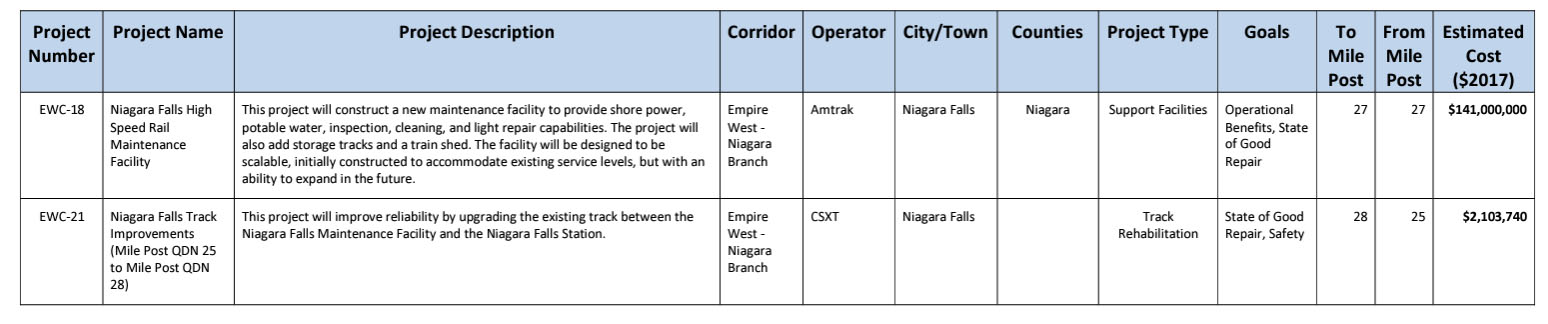

A new Buffalo-Depew Station would be constructed with a new high-level platform and new interlockings, serving new third and fourth passenger tracks. The Exchange Street and Niagara Falls stations having been recently been rebuilt, will see little additional work. On the site of an existing freight yard, a new Niagara Falls Maintenance Facility is being planned; to provide shore power, potable water, inspection, cleaning, and light repair capabilities. The facility will include storage tracks and climate control buildings, as opposed to the current situation where train maintenance is conducted by Amtrak personnel outdoors in the elements.

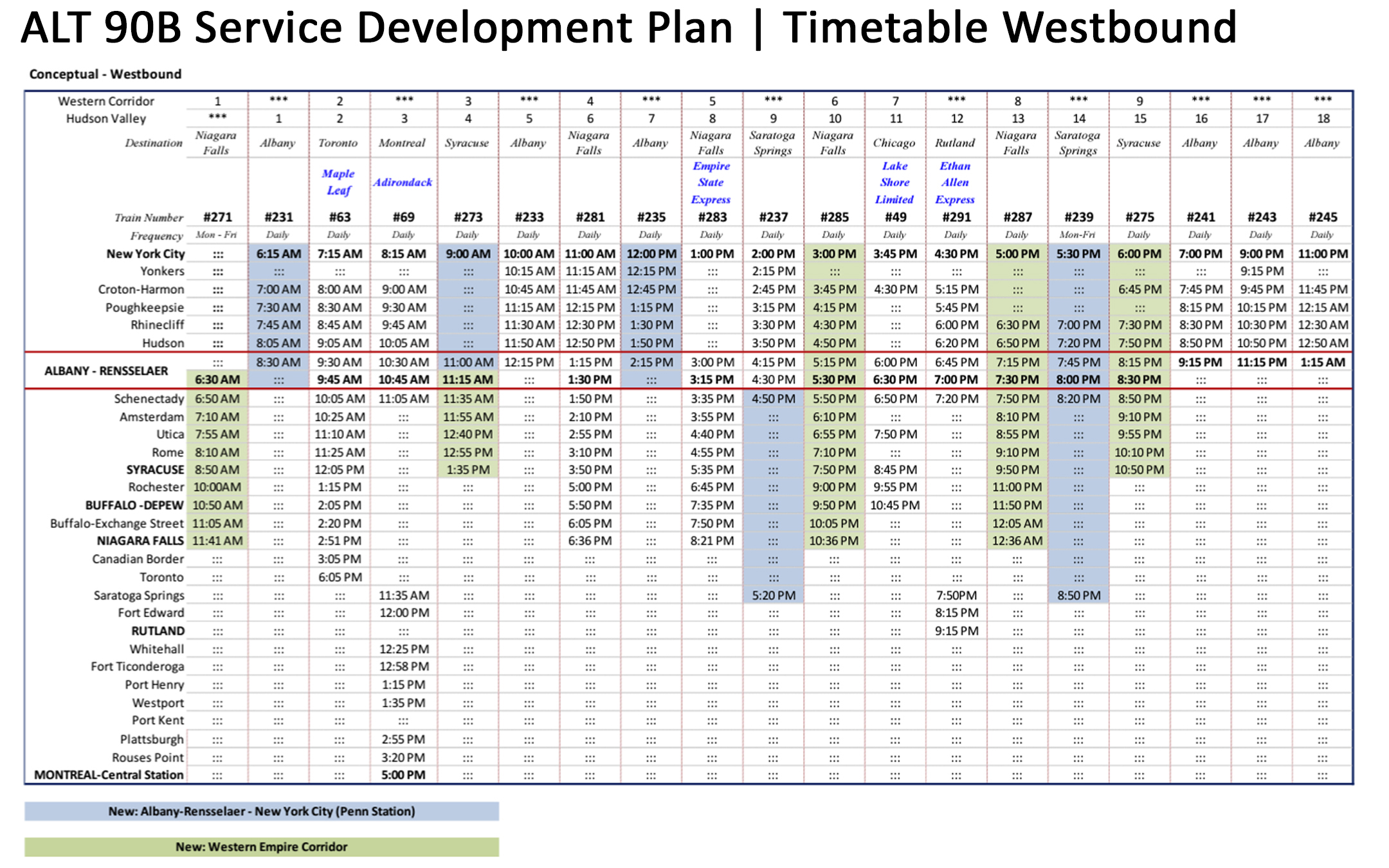

Alternative 90B would double the frequency of Amtrak’s service west of Albany to nine daily round trips to Syracuse, eight of which continue to Buffalo-Depew including the ‘Lake Shore Limited’, and seven on to Exchange Street and Niagara Falls. Travel times between Albany-Rensselaer and Buffalo-Depew would be reduced from the current best of about around 5h 15m to 4h 20m, for an average speed of 67-mph, with an on-time-performance of 95 percent.

Express Trains

How to Reduce Travel Times Even Futher than the Current ALT 90B Service Development Plan

There are two ways to reduce the travel times of passenger trains, run faster and stop less, including at intermediate stations. As laid out in the Service Development Plan of Alternative 90B, travel times are primarily lowered by traveling at a slightly faster (90 vs. 79-mph) top speed and not slowing or stopping for freight trains. Skipping stations with limited-stop express trains could significantly lower travel times even further between large destination cities, beyond what is proposed in the ALT 90B Service Development Plan.

The problem with express trains is that while they would enhance service to a few large cities, smaller cities would be left with an inferior service, not only of longer travel times, but of fewer daily trains, as the expresses ran non-stop through their stations. Politically this would seem to be a serious issue, with local boosters and elected officials likely crying foul.

The solution is however fairly simple, just run more trains, with any limited-stops express trains being in addition to the proposed eight daily Empire Corridor trains laid out in the Service Development Plan. So as long as all stations see increased frequency and significantly reduced travel times, with departures and arrivals spaced evenly throughout the day, then there should be no political issue with running a few limited-stop express trains. Instead, further reducing travel times between New York City, Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls should increase political support.

Extrapolating from these two examples suggests that a total maximum of 45 minutes could be cut from the travel times between New York City and Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls by running non-stop north of Croton-Harmon—skipping Poughkeepsie, Rhinecliff, Hudson, Albany-Rensselaer, Schenectady, Amsterdam, and Rome, with passing non-stop through Rensselaer saving 15 minutes from the standard scheduled layover to change crews while detraining and boarding passengers. This would require the express run to be operated by a single crew (engineer, conductors, and café attendant) between New York City and Niagara Falls.

This would reduce travel times from New York City to Syracuse from the projected 4h 50m in the Service Development Plan, to 4h 05m, for an average speed of 71-mph. The average speed between Croton and Utica for a non-stop run of 259 miles would be 82-mph, for a travel time of 2h 30m. Travel times from New York City to Rochester would be reduced from 6 hours to 5h 15m, and for Buffalo-Depew from 6h 50 to 6h 05m. Running express trains non-stop pass Albany would also help remediate the current issue of fully sold-out trains New York-Albany reducing seats available west of Albany.

The reduction of travel times from New York City to Utica, Syracuse, and Rochester to 3h 15m, 4h 05m, and 5h 15m is significant as rail journeys of 4-to-5 hours are seen as competitive with air travel in Europe. Historically in the Postwar Era travel times of 3 hours by intercity train became to be seen in the 1970s as the threshold of competitive-ness with airlines by rail experts, an express train being able to travel from city center to city center while air travelers lost time traveling to and from airports and checking in for their flight. A three-hour travel time was seen as very conducive to out-and-home day trips, particularly by business travelers, for a total travel time of six hours allowed for an eight-hour workday in a distant city and ten hours of rest at home.

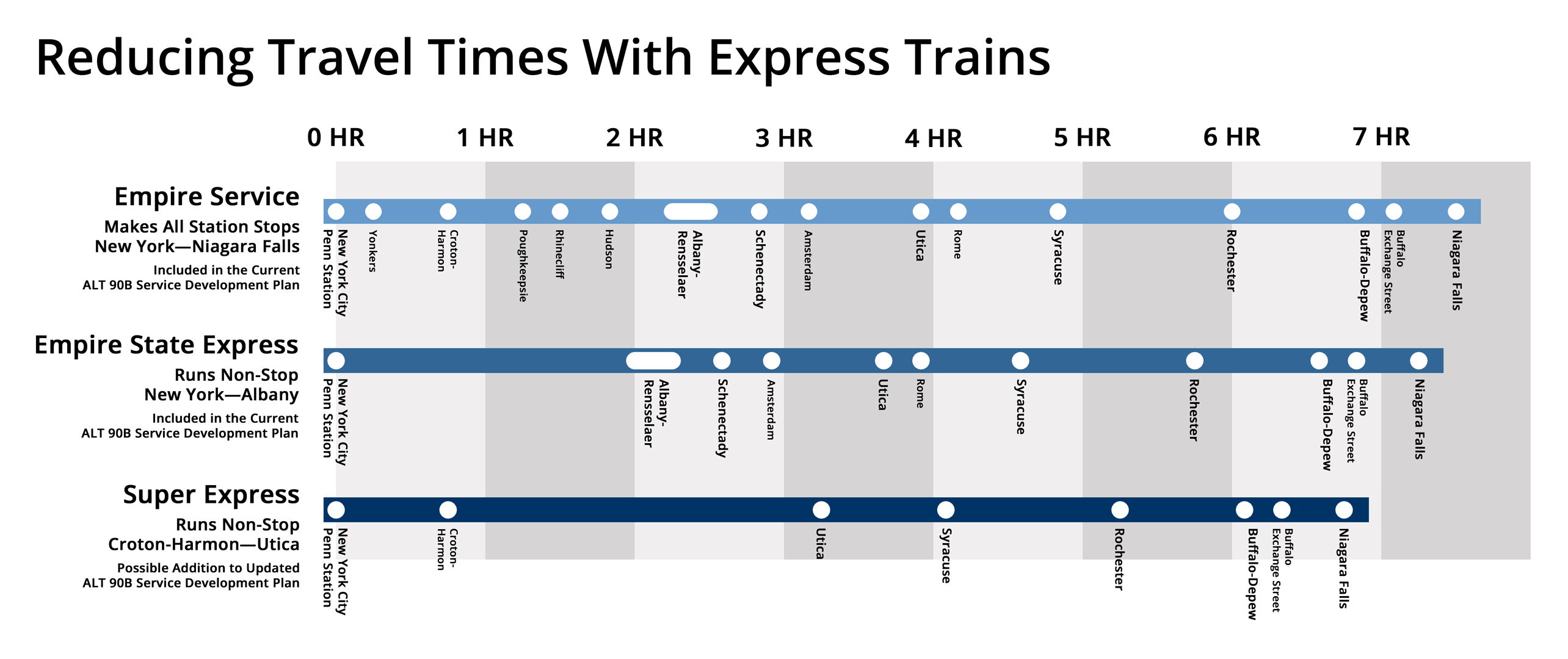

ABOVE: An infographic illustrating the reduction in travel times between major destinations by skipping intermediate stations for some limited-stop express frequencies. The top two train frequencies – Empire Service and Empire State Express – are included in the ALT 90B Service Development Plan, the bottom “Super Express” is a possible express service that could be included in an updated Service Development Plan.

ABOVE: An infographic illustrating the reduction in travel times between major destinations by skipping intermediate stations for some limited-stop express frequencies. The top two train frequencies – Empire Service and Empire State Express – are included in the ALT 90B Service Development Plan, the bottom “Super Express” is a possible express service that could be included in an updated Service Development Plan.

BELOW: An modified timetable from the Service Development Plan, modified to include three additional roundtrips between New York City and Niagara Falls, including new morning and evening expresses—in addition to several existing semi-express frequencies—and an overnight red-eye service, which existing overnight bus service between New York and Buffalo by Greyhound and FlixBus indicates there is a sizable travel market for intercity rail to serve as well.

ALT 90B Empire Corridor Modified Express Timetable PDF

ABOVE: The CSX Mainline alongside the Mohawk River at Lock E10, east of Amsterdam. Passenger Rail is the both a substainable and scenic way to travel, and needs to be better included in New York State's climate planning.

Climate Act

In Spring 2019 the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act was passed and signed into law, mandating that New York State move to a net-zero emission economy by 2050 by eliminating most emissions of greenhouse gases – primarily CO2 – from the burning of fossil fuels.

The goal is to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 85% of 1990 levels by 2050, with the remaining 15% offset by reforestation, wetland creation, or carbon capturing through technological means. A 22-person “Climate Action Council” composed of top state officials, advised by smaller working groups with expertise in specific areas, was created to develop the framework for how the state will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Unfortunately, the Empire Corridor Tier One EIS does not address the Climate Act as most of the work in completing it was done before 2019, despite the long-delayed release of the Final EIS in February 2023. The Final Scoping Plan released by the Climate Action Council on January 1, 2023 doesn’t address rail either, its only mentioned in the Transportation Chapter being: “For the purposes of the scoping discussion, public transportation includes but is not limited to transit, micro-transit, shared mobility, and longer distance passenger rail services.” The Climate Council focused primarily on electrifying motor vehicles, including freight trucks and public transit buses. Electrification of the remaining diesel operated MTA commuter rail services of the Metro-North and the Long Island Rail Road was even overlooked!

It seems that for intercity rail New York State is outsourcing—if more in practice than plan—to the Amtrak, the service provider, which has committed to becoming a net-zero mobility provider by 2045, issuing in April 2024 a Request for Information (RFI) for solutions to transforming its rail fleet with zero-emission technologies.

On an intern basis Amtrak is moving towards replacing conventional diesel fuel with Renewable Diesel, a biofuel created from a blend of vegetable oils, animal fats, or recycled restaurant grease—reducing lifecycle carbon emissions by up to 63%, while also reducing other harmful emissions, including fine particulates and nitrogen oxides, leading to improved local air quality. California’s state-supported Amtrak services—the ‘Surfliner’, ‘Capitol Corridor’, and ‘San Joaquin’—are now fueled with biodiesel derived from commercial kitchens. Because Renewable Diesel is chemically identical to petrol-eum diesel, it is a “drop-in” fuel that can be used in existing diesel engines without modifications, either fully replacing diesel or being blended with any amount.

Long-term Amtrak is looking at hydrogen fuel cells, working in a hybrid powertrain with batteries. Green Hydrogen produced from renewable power generation—wind, solar, and hydro—is a zero-emission fuel, as opposed to hydrogen produced from fossil fuels, currently the primary industrial source. Hydrogen fuel cells are still a maturing technology in limited use, and the environmentally sustainable and cost-effective production of green hydrogen is also a work-in-progress. However, progress is being made with a lot of research and development, backed by both public and private funding being undertaken to develop a “hydrogen economy”.

Caltrans (California Department of Transportation) has the goal of achieving zero emissions by 2035 for its state supported passenger rail services, and is primarily pursuing hydrogen fuel cell propulsion to do so. Caltrans has rejected electrification with overhead catenary as too expensive (host freight railroads also are on record in strong opposition to electrification) to install, with batteries having too short a range. Caltrans has already ordered six zero-emission hydrogen trainsets from train manu-facturer Stadler Rail for their new Valley Rail regional passenger service. Freight railroads CPKC and CSX are also currently testing prototype hydrogen locomotives converted from existing diesel-electric locomotives, the hydrogen fuel cells and battery pack replacing the diesel prime mover.

While Caltrans rejected electrification due to the high initial capital cost of installation and opposition by the freight rail industry, it has considered “tri-mode” hydrogen-battery locomotives making use of “discontinuous electrification”, utilizing a pantograph to take electricity directly from overhead catenary wire, where installed on publicly controlled track, for powering the traction motors and recharging the batteries.

Lastly, the Preferred Alternative 90B supports the Climate Act’s goals of encouraging “Smart Growth” and “Mobility Oriented Development” of walkable, compact, mixed-use projects of higher density, preferably within walking distance to a public transit facility. Modern intercity passenger rail encourages sustainable cities by serving as an urban renewal catalyst for the walkable higher density development of “Transit-Oriented Development” around rail stations, many of which along the Empire Corridor are located “downtown” in historic urban centers. Alternative 90B by utilizing existing railroad infrastructure and right-of-way, will preserve farmland and the wildlife habitat of forests and wetlands, while also reducing carbon emissions during construction by avoiding excessive tree cutting and excavation of earth, an environmental plus over greenfield high-speed rail.

New York State Climate Act | Website

Amtrak Issues Zero Emission Technology RFP

Amtrak’s Net-Zero Strategy | Webpage

ABOVE: Rendering of new 'Airo' Trainset ordered by Amtrak from Siemens Mobility for its Northeastern corridor services.

New Trains

In December 2022 at a press conference in the Moynihan Train Hall at Penn Station, Amtrak President Roger Harris and other officials introduced the new brand name “Airo” for the Siemens Charger-Venture intercity trainsets of semi-permanently-coupled coaches, making up a fleet of 83 trainsets that would replace the decades old Amfleet coach consists for the corridor services in the Northeast, Southeast, and Northwest.

The Empire Corridor services—‘Empire Service’, ‘Maple Leaf’, ‘Ethan Allen’, and ‘Adirondack’—will utilize a fleet of fifteen (with an option for two more sets) hybrid battery trainsets. These trainsets will have a Siemens diesel-electric ALC-42E Charger (the diesel engine providing the power for the traction motors) locomotive mated to an Auxiliary Power Vehicle (APV) adjacent to the locomotive, the APV containing a large battery pack to supply electrical power when operating in Penn Station, and Grand Central Terminal if required in the future.

The APV will part of a semi-permanently coupled consist of six Siemens Venture coaches, the rear coach having a streamlined cab for push-pull bidirectional travel, simplifying and speeding up turnarounds at terminal stations. The battery will eliminate the current use of DC third rail by the existing fleet of aged eighteen GE Genesis P32AC dual-mode engines. A prototype Empire Corridor Airo trainset is planned to be available for testing by 2025, with the rest of the trainsets being delivered by 2030.

The Airo trainsets will have modern train interiors. The coaches will feature a spacious interior with panoramic windows, enhanced lighting, improved technology with digital customer information systems, touchless restroom controls, dedicated individual outlets, USB ports, and onboard WiFi. Wayfinding signage will become cleaner and more evident way to identify and differentiate cabins—both on the exterior and interior of the coaches through a color-coded system.

Seat design will prioritize ergonomics, offering enhanced comfort with plenty of legroom, bigger and sturdier tray tables, moveable headrests and a dedicated cup and seatback tablet-holder. The seating will be in two classes, coach with 2x2 seating and business with 2x1 seating. The trainsets will also meet or exceed all requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for new-build equipment, replacing legacy equipment built prior to the ADA’s passage on which various accessibility elements have been added during overhauls with varying effectiveness.

When operating in diesel mode, the new trainsets will meet EPA Tier 4 emissions standards. The Charger locomotives are equipped with electronically-controlled regenerative braking systems that use energy from the traction motors during braking to feed the auxiliary and head-end power systems to minimize fuel consumption. With a fuel capacity of 2,200 gallons, the locomotive consumes more than three times less fuel than comparable gallons per passenger for two-person car travel. The QSK95 Cummins engine in the locomotives provides a 16 percent improvement in fuel efficiency over the non-Tier 4 certified locomotives that the Charger will replace. The battery power may also further boost the fuel efficiency, as with hybrid motor vehicles.

Introducing Amtrak Airo, a Modern Passenger Experience | Webpage

ABOVE: An evening train from New York City departing Exchange Street Station in Downtown Buffalo for Niagara Falls.

Moving Forward

Many will be disappointed that Alternative 90B is not “true high-speed rail”, yet this “higher speed rail” program has the big benefit of avoiding the pitfalls that have befallen California High Speed Rail and the Texas Central Railway. The 2014 Draft EIS examined and rejected two alternatives for 160 and 220-mph high-speed rail, due to their high estimated cost of $27 and $39 billion, costs which are likely an underestimate given that the cost estimate for the Phase 1 San Franciso-Los Angeles segment of the California HSR project has gone from $33 billion in 2008 to $106 billion in 2024, with the completion date slipping decades into the future. Building a new greenfield high-speed railway between New York City and Buffalo would in all likelihood cost well over $50 billion and take several decades to complete.

By leveraging the surplus right-of-way of the existing historic rail corridor, ALT 90B avoids the land acquisition problems of the greenfield high-speed rail construction of California HSR and Texas Central, where rural property owners have legally and politically fought eminent domain proceedings for years, delaying construction while increasing costs. Brightline West, now under construction between Las Vegas and the Inland Empire, avoids this issue by utilizing the median of Interstate 15 from for the new high-speed tracks. However, the terrain and built environment of Upstate New York is very different from the Mojave Desert, the alignment of the NYS Thruway through the Hudson and Mohawk valleys having sharper curves and steeper grades than the existing railroad mainline.

A good model for the Empire Corridor is Brightline Florida, a privately owned and operated intercity passenger railroad owned by the Fortress Investment Group. The civil engineering works compiled by the ALT 90B Service Development Plan are equivalent to that undertaken by Brightline, where some 200 miles of a formerly doubled but now single-track freight line, was doubled-tracked again utilizing the surplus right-of-way, with 35 miles of new track built along a state expressway from Cocoa to Orlando International Airport. From the project announcement to the inauguration of full-service Miami-to-Orlando, Brightline took only a decade to be built in two phases—with second phase of 170 miles from West Palm Beach to Orlando taking only 5 years to be built at the cost of $5 billion.

Other states are moving forward with “higher speed rail” programs, including Virginia and North Carolina, which are building out the “Southeast Corridor” from Washington DC, south through Richmond, Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro, and Charlotte. From Washington to Richmond, a third (and some segments of fourth) 90-mph dedicated passenger track will be built alongside the existing CSX mainline, while from Richmond to Raleigh a mothball freight line would be rebuilt for 110-mph passenger service. Both states have received billions in federal grants, matched with billions in state funding, overseen by competent and well-staffed state rail agencies.

Alternative 90B represents a “good enough” plan that would deliver significant improvements in long-distance mobility and environmental sustainability, at a cost to construct that New York State can afford, and in a timeframe short enough to be relevant to the lives and plans of people today. Let’s not wait anymore, let’s build a new Empire State Express for the 21st Century.